A decade of change – can we still get to net-zero by 2050?

The Energy Technology Perspectives is one of the International Energy Agency’s flagship publications. It complements the World Energy Outlook, which focusses more on the energy mix while the ETP focusses on technologies and pathways to reach international climate energy goals. We take a look at major changes between this year’s report and the 2010 version to better understand how the energy scene has changed in a decade.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) produces a range of publications about the status and future of the global energy sector, sometimes delving into greater detail for different geographical regions or countries. In September 2020, the IEA published the latest of its biannual Energy Technology Perspectives reports. The projections in that report were updated in the release of the 2020 World Energy Outlook, which includes additional scenarios and a bigger focus on the impacts of COVID-19.

There are some interesting insights to be gained from comparing the IEA’s 2010 analysis with the technology mix and decarbonisation goals explored in the most recent report.

What does 10 years mean in the energy sector?

Ten years represents about one fifth of the lifetime of a coal fired power station but generally the full life expectancy of household electrical appliances. In a decade we cycle through three federal governments – which can deliver disruptions in energy and climate policies. In the past 10 years we have seen enormous technological advances and energy disruption – the rise and rise of rooftop solar for example – but much has also stayed the same.

A common element of the 2010 and 2020 report is they were both published following an economic downturn. The 2010 analysis followed the Global Financial Crisis, and the 2020 report was produced during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Both economic crises resulted in short term emission reductions, but the most recent are expected to be short-lived unless these is significant further structural change to the energy system. This change has been occurring over the past decade supported by the global Paris Agreement on climate change, signed in 2016. There are now 189 parties to this agreement.

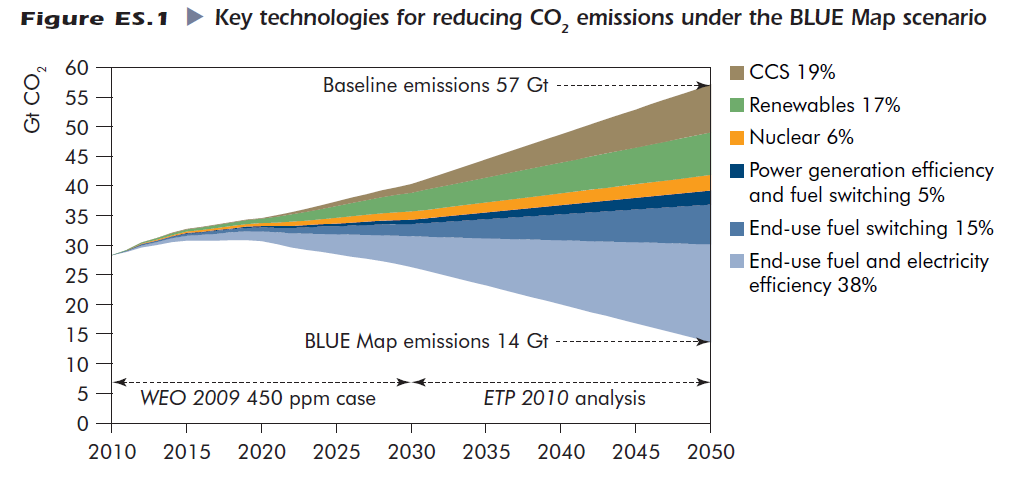

The leading figure of the 2010 report is highlighted below. This shows a reference scenario – emissions in the absence of policies to decarbonise the global economy and a BLUE Map Scenario (BLUE), which was consistent with long-term global rise in temperatures of between 2 to 3°C. Within this BLUE scenario, a range of technologies and a level of deployment were identified to reach the emission target.

Figure 1: ETP2010 emission scenario (Source: OEACD/ IEA (2010), Energy Technology Perspectives 2010)

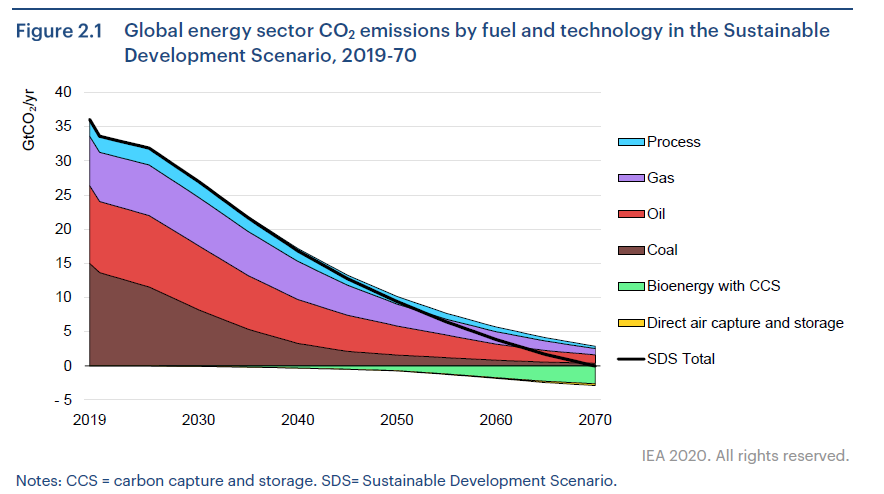

In the more recent publication, the IEA has moved away from showing a reference scenario and is focused on a sustainable development scenario (SDS), consistent with reaching global net-zero CO2 emissions by about 2070. This scenario sets out the major changes that would be required to reach the key energy related goals of the UN Sustainable Development Agenda, which covers meeting the Paris agreement, universal access to modern energy and reduction in energy related air pollution.

Figure 2: ETP2020 Emission trajectory for Sustainable Development Scenario (Source: OECD/ IEA (2020), Energy Technology Perspectives 2020).

There are a couple of differences between these sets of scenarios. Firstly, the 2010 reference scenario indicated that energy related emissions would be about 34 Mt CO2 by 2020. In the 2020 report, the starting point is more than 36 Mt CO2 from the energy sector, showing that emissions have continued to increase over the past decade – in spite of the Paris Agreement. The level of ambition has also increased. While the 2010 BLUE map scenario aimed to limit a long-term temperature rise of two to three degrees, the 2020 scenario is more consistent with the 1.5°C long-term temperature rise:

If CO2 emissions were to fall below net-zero after 2070, then this could increase the possibility of reaching 1.5°C by the end of the century, depending on the level of carbon removal eventually reached. (IEA, Energy Technology Perspectives 2020, pg 67)

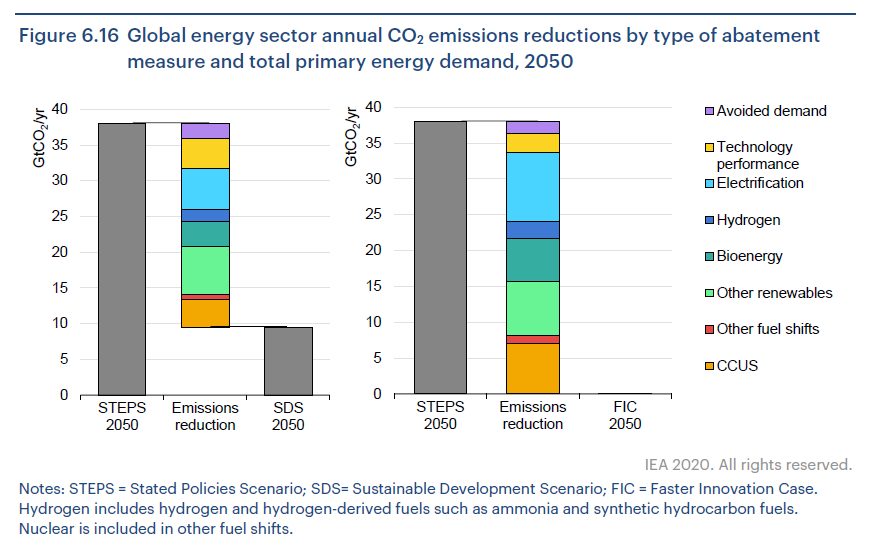

Figure 3: Technology mix in the Sustainable Development Scenario (Source: OECD/IEA (2020), Energy Technology Perspectives)

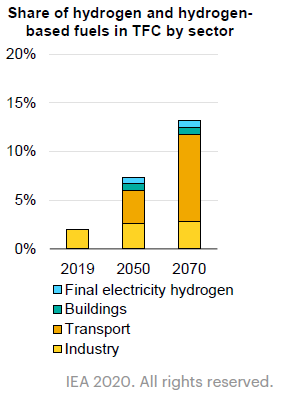

The technology mix to reduce emissions has also changed significantly. In 2010, there was major emphasis on carbon capture and storage (CCS), nuclear and energy efficiency. The 2020 report shows that more renewables and bioenergy will be used. The SDS shows much less energy efficiency improvement as this is assumed to be incorporated into the stated policy positions. The contrast for CCS is significant, with a projected share of 9 Gt in the 2010 publication reduced to just over 3 Gt in the 2020 report. This is mainly due to decarbonisiation leading to more renewable generation instead of ongoing use of coal with CCS. Furthermore, CCS is also applied to bioenergy in the 2020 report allowing emissions from hard-to-decarbonise sectors to be offset. The 2020 report also introduces hydrogen as a low emission technology – although mostly applied to transport and heavy industry.

Figure 4: Share out hydrogen in total final consumption by sector (Source: OECD/ IEA (2020), Energy Technology Perspectives 2020)

Contrary to many countries and local regions that are setting net-zero targets for 2050, the SDS does not reach net-zero until 2070 and shows fossil fuels continuing to be used in the 2070 timeframe. This partly reflects that it takes time for new technologies to become deployed at scale. Even with the strong growth in renewables for power generation, there is still a long way to go to decarbonise the entire energy sector, especially noting that electricity only represents about one third of global energy emissions. The report also provides a scenario where net-zero emissions from energy are reached by 2050. Nevertheless, in each case, a transition to net-zero takes many decades.

Is scenario planning worthwhile?

Do these types of scenario reports actually deserve our attention given the major changes across 10 years of work? Absolutely. This type of scenario modelling encourages conversation about the effort required to reach net zero emissions and to better understand the interlinkages between policy, technology development and emission outcomes.

Revising scenarios is essential to take account for changing policy settings (e.g. Germany banning nuclear power generation) or changing technology developments (e.g. hydrogen cost reductions). These types of tools should be more widely used to influence policy and identify which policy levers are required to facilitate the net-zero transition. The question of whether we can get there by 2050 is an open one but work such as this by the IEA is an important check and balance as we continue on the decarbonsation journey.

The IEA Energy Technology Perspectives is a comprehensive report and well worth a read to learn more about energy technologies and their role to reduce emissions.