Is SA at critical solar?

In May, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) completed a report[i] on South Australia’s minimum operational demand thresholds. Undertaken at the request of the SA Government, this report was supported with information from SA Power Networks (SAPN), the state’s Distribution Network Service Provider (DNSP).

At a high level, it is a review of the significant impact that distributed residential and commercial solar photovoltaic (PV) is having on the electricity system and how it is impacting the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) ability to maintain system stability in South Australia.

What is the problem?

According to the report, there are two key challenges.

- Distributed PV: Solar PV effectively ‘hides’ the amount of load that a household or business uses by the amount that it generates. This means that during times of high solar generation, a typical house can draw very little (and sometimes no load) from the grid. The scale of Solar PV has now reached such a level that AEMO believes it will significantly impact system stability if it is disconnected by voltage disturbances. A simple analogy might be trying to keep two people balanced on each end of a seesaw, but not knowing if one of them might suddenly decide to jump off and upset the balance.

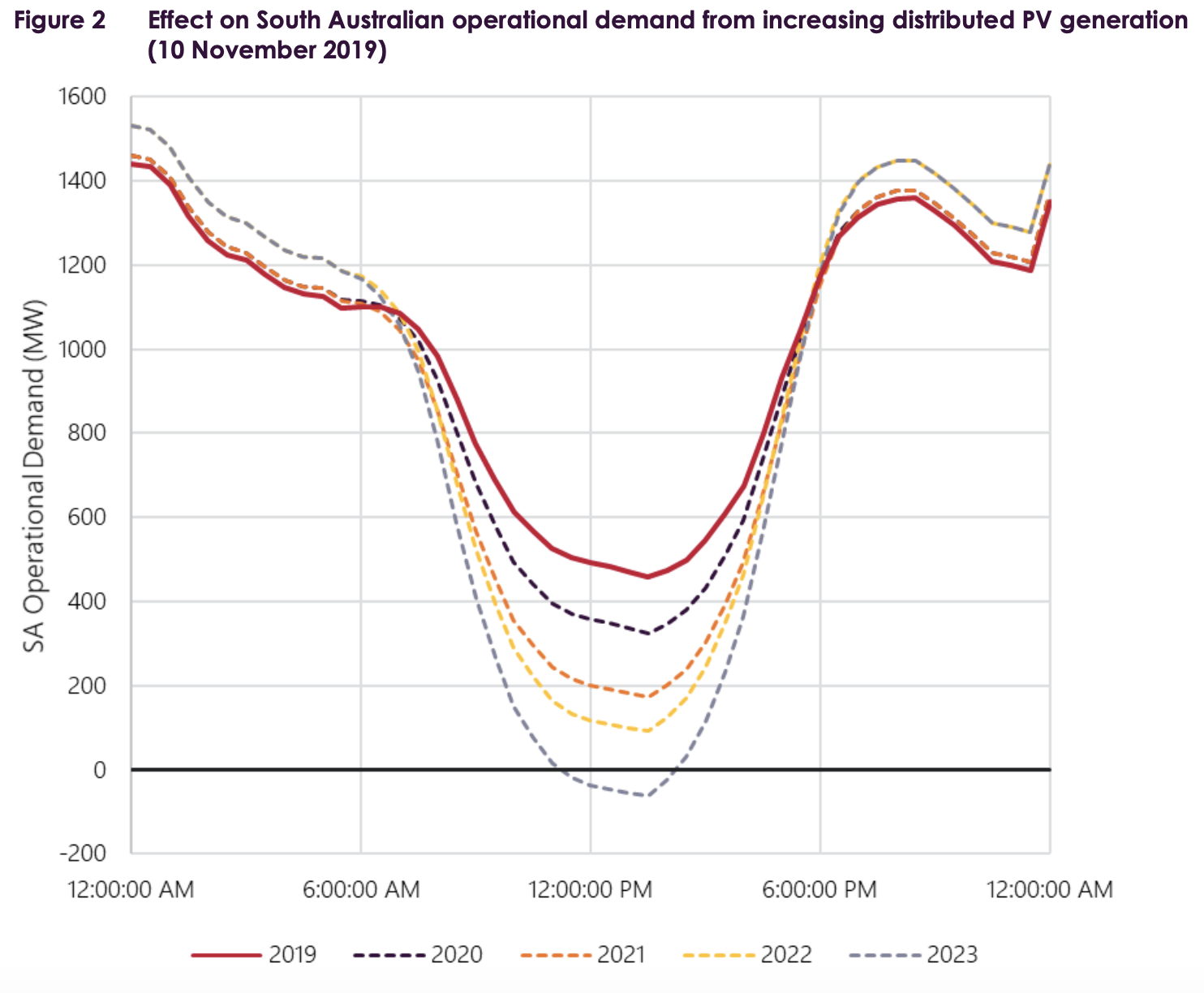

- Whenever South Australia (SA) ‘islands’ or disconnects itself from the rest of the National Electricity Market (NEM) there is a minimum amount of load that AEMO believes is required to provide system stability. AEMO estimates this minimum amount to decrease from 550MW in 2020 to 450MW by 2021 and notes that it reached a low of 458MW back in 2019. In the report, AEMO states that due to the scale of Solar PV now and in the future, it should have the ability to control DER export into the grid to ensure minimum demand doesn’t fall below these thresholds.

| What is Operational Demand?

This is the aggregate amount of power that is supplied by scheduled, semi-scheduled and non-scheduled generation. One of AEMOs responsibilities is to balance the demand of the grid and supply from large-scale generators. |

Figure 1: Effect on SA operation demand[ii]

As shown in the graph from the study, SA’s operational demand is forecast to fall year on year due to Solar PV uptake.

We’ve talked about minimum (operational) demand before[iii]. Rooftop solar PV provides not only enough local generation for the household beneath the roof but also the excess is exported and used locally. This excess means there is less need for large generators. However, those large generators also provide critical support to the system, keeping it stable. If we don’t need any of those large generators to provide the electricity we use, then they are not there to support the system.

What solutions are being discussed?

The SA government is consulting stakeholders about a range of regulatory changes that it is proposing in order to address the issues raised in the AEMO report[iv].

One of the proposed solutions is the so-called “back-stop” mechanism which has recently caused some stir among distributed energy resource (DER) owners[v]. This would allow AEMO (via the DNSP) to turn off DER during emergency events to protect the electricity system.

While this capability makes sense in principle given SA’s circumstances, we should be careful that it’s used only in the direst events and not as a business-as-usual tool. These are, after all, customer assets and the impact on them from overuse of this tool would be significant.

Another way to manage increased electricity generation from solar PV is to increase demand, rather than turn off generation. We’ve talked about “footroom” before, which pays customers to use more electricity.

SAPN is exploring this option with its “solar sponge” tariff. This is a special rate that incentivises customers to increase their usage during times of maximum solar generation and help keep minimum demand issues at bay.

For instance, customers could be paid to charge their electric vehicles or run their air conditioners, and this increase in demand would “soak up” the surplus generation from solar PV at midday.

Using DER in this way has significant benefits for customers and networks, and wide-spread adoption would help cost-effectively manage issues like minimum demand.

Looking forward

Some things we should keep in mind while we address the short term and plan for the long term:

- Be clear on the distinction between urgent and important – urgent things must happen now, like voltage ride through settings for South Australia. An example of an important thing is how we develop a long-term solution that makes sense socially and economically for the rest of the NEM. Very few long-lasting and good answers to important issues are made urgently. This is why we have such a robust rule change process that gives people the time to think.

- We should focus more on problems, not solutions – clearly articulating problems is what gives better solutions, not shoe-horning urgent solutions onto important problems. What might help is developing a clear and detailed list of requirements over a set time period and leveraging the market to propose efficient solutions.

If you are interested to contribute further to the discussion in SA, I encourage you to read the consultation papers and make a submission to the Department of Energy and Mining[vi].

References

[iii] https://www.energynetworks.com.au/news/energy-insider/2020-energy-insider/changing-demands/

[iv] http://energymining.sa.gov.au/energy_and_technical_regulation/energy_resources_and_supply/consultation_on_regulatory_changes_for_smarter_homes

[v] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-20/concerns-over-plan-to-switch-off-household-solar-panels/12267162

[vi] http://energymining.sa.gov.au/energy_and_technical_regulation/energy_resources_and_supply/consultation_on_regulatory_changes_for_smarter_homes