Negative oil prices = lower electricity prices?

Oil prices went negative for the first time in history last week with May futures contracts for US West Texas Intermediate crude oil falling to never-before-seen lows.

At least, in theory, you were able to pick a barrel of crude oil last week – and be paid for your troubles! Flatlining industrial demand fuelled by the COVID-induced US industry shut down led to storage facilities reaching capacity and having nowhere to store oil.

Although the circumstances were local, the effects were global as the price of Brent crude oil futures fell sharply with West Texas Crude futures after already trending consistently down over the past two months[i]. In great news for hip pockets, this could eventually have flow-on effects of reducing energy bills.

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) prices tend to follow Brent crude oil prices but with a lag of about three months[ii]. Australian natural gas producers have numerous avenues to sell and use their gas, including:

- exporting natural gas as LNG, or

- supplying the domestic natural gas market, or

- using the gas in gas-fired electricity generation plants.

If the attractiveness of exporting LNG falls in line with global LNG prices, options two and three starts to look much more attractive. With more gas staying onshore, we might expect downward pressure on wholesale gas prices and a reduction in gas-powered electricity generation costs, which could also lead to lower electricity generation costs.

The extent to which cheaper natural gas prices influence electricity wholesale prices largely depends on how often gas generators running on cheaper natural gas can displace other, now more expensive forms of generation in the wholesale electricity market.[iii]

Lower wholesale gas and electricity prices will mean lower bills for customers as long as these savings are passed through to retail prices.

DER impacted

The rapid descent in oil prices serves as an interesting example of how interlinked the energy market can be. Falling wholesale electricity prices, from any oil price effects of simply lower demand, could, for example, even influence the path of investment in Distributed Energy Resources (DER). If lower oil prices do lead to a fall in wholesale electricity costs and the end-use electricity tariffs, the value of electricity produced and consumed by solar PV will fall, making it less likely that households and businesses will invest in DER.

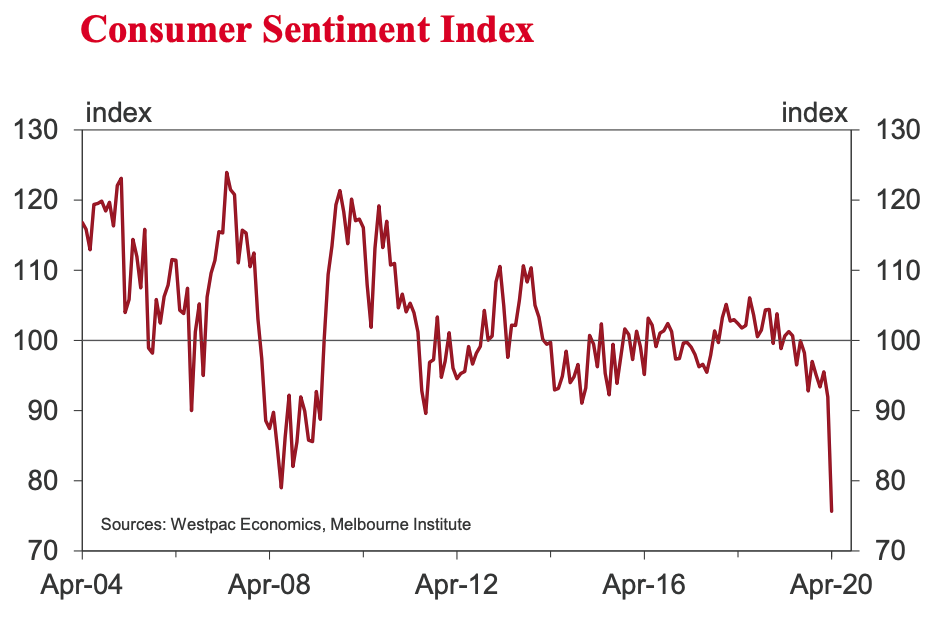

Households and businesses are doing it tough with COVID slowing small businesses to a standstill and placing huge pressure on households. With an expected June unemployment rate of 10 per cent, consumer confidence is down to levels lower than those seen during the Global Financial Crisis.

Non‑essential spending – particularly on large capital items – is likely to dry up and limit investment in DER.

Figure 1 – Westpac Consumer Confidence Index (Source: Westpac Bulletin, Consumer confidence collapses as Coronavirus hits hard, 15 April 2020)

DER investment is down, but the ability to produce and install DER technologies is also likely to have fallen as well. Producing DER equipment has benefited from global economies of scale as countries with lower production costs than Australia take advantage of economies of scale and mass produce DER equipment.

DER equipment could become relatively more difficult to access with some borders closed and supply chains disrupted. Additionally, the qualified personnel who would be safely installing the equipment to ensure it is operating appropriately may, in some cases, be unable to work due to COVID restrictions.

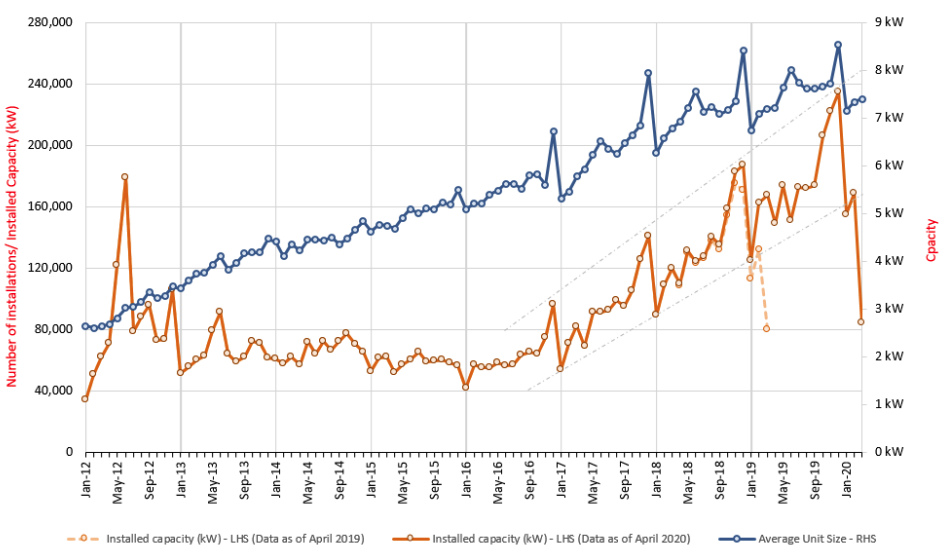

However, more households are working from home and are benefiting in the short term from self-consuming a higher proportion of electricity from their DER. Despite the incentive of better utilisation, working from home doesn’t seem to be a strong enough incentive to spur investments in DER as new solar installations in March seem to have plummeted, though March installation data may still be trickling in.

Figure 2 – Monthly installations, installed solar PV capacity & average system size Jan 2012 – Mar 2020 (Source: Clean Energy Regulator data, Australian Energy Council analysis, data as of 31 March 2020)

DER take-up at risk?

While it’s clear DER uptake rates have fallen, the exact factors at play are opaque. For the moment at least, precise DER uptake rates have become more uncertain and dependent on factors outside of its traditional growth drivers.

If the repercussions of COVID persist, it’s likely that the trajectory of DER uptake will be noticeably impacted.

The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) produces a few different scenarios that attempt to model DER uptake in different economic, policy and technology conditions. The ‘central’ scenario reflects current policy settings and technology trajectories, where the transition from fossil fuels to renewable generation is led mainly by market forces. There are other upward and downward scenarios, for example, the ‘step-change’ scenario with aggressive decarbonisation targets and strong technology improvements, or the ‘slow change’ scenario where economic conditions are challenging, investment is lower and living standards are protected over pursuing structural reform.

There’s no doubt that over the last couple of months there’s been a broad economic shift towards the ‘slow change’ scenario, but the scale and persistence of the shift remains to be seen. We’ll have to wait until the dust settles before we have a better picture of how DER uptake is likely to track in the months and years ahead.

Reference

[i] https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/future/brnm20?countrycode=uk

[ii] https://eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/7249.pdf p. 2.

[iii] The marginal price of electricity is the highest bidding price that will meet all electricity demand in the market after all lower priced bids have been accepted.