Rules to make ISP investment add up

The proposed Transgrid and ElectraNet rule changes are designed to address a potentially critical financing issue arising from applying the current framework – an issue which has the potential to undermine the timely delivery of identified electricity transmission projects in AEMO’s 2020 Integrated System Plan.

Both rule change proponents, Transgrid and ElectraNet, are involved in large greenfields interconnector projects to underpin AEMO’s agreed ‘actionable’ blueprint for optimum grid development to support reliable and competitively priced energy for customers.

Matching the framework to the need

The existing regulatory framework is largely designed around mature networks which feature small, constant incremental investments to connect, for example, new estates of large business customers. Indeed, Australia has not seen a major new transmission project of the scale of those envisaged in the ISP for more than a decade.

As an example of the different circumstances presented by these larger projects, Transgrid’s Project Energy Connect is expected to represent about $2 billion of greenfields investment. This is compared with an existing regulatory asset base of about $6 billion for the company. Over the next ten years, some $9–10 billion of new transmission investment is identified as required to be delivered in NSW alone.

The additional rule proponent, ElectraNet, is also planning to make supporting investments for the South Australian elements of the new grid link. Added to new projects for Eyre Peninsula and synchronous condensers, these will also represent major new investments compared with its existing asset base.

Identifying the problem – what’s the issue?

Put simply, the regulatory system in place was not built to accommodate one-off investments of this size.

Applying its current rules and default models to large greenfields projects produces outcomes that make efficiently financing the project highly problematic.

For example, the practice of “indexing” the regulatory asset base for inflation has the effect of skewing cost recovery so far towards the end of the project life that securing lower cost investment grade financing becomes highly doubtful.

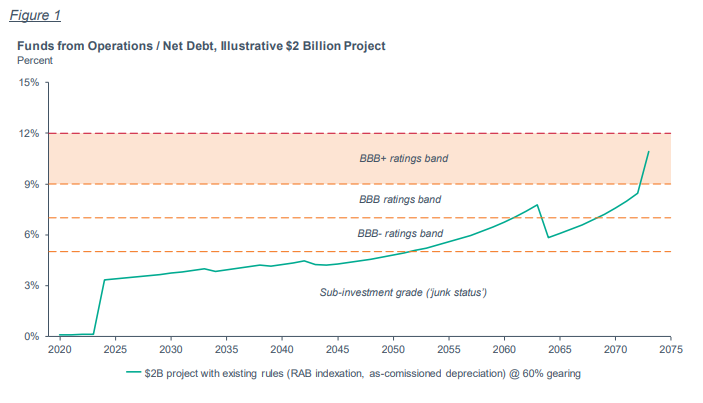

As Transgrid’s modelling indicates, applying this indexing approach in a ‘cookie cutter’ fashion to a project with high upfront build costs results in revenue profile that is insufficient to meet even the minimum investment grade debt benchmarks for 30 years. The regulatory frameworks assumes a BBB+ benchmark for 50 years, but on a project basis the returns align with junk bonds status (see Figure 1)

Figure 1: The long wait? Projected funds from operation / net debt for illustrative $2b project. (Source: Transgrid Submisson: National Electricity Rules change proposal –Making ISP projects financeable – Participant Derogation)

Bending the road to cost recovery – a possible fix?

The major way the rule changes tackle this problem is to adjust the timing of revenues – by removing the deferral of cashflow that is caused by indexing the asset base of the greenfields project by inflation.

Importantly, this does not change the present value of transmission charges paid by customers over the project. It effectively represents just a small earlier payment of costs incurred. It’s like paying off slightly more of a home loan early, it reduces the amount paid in the future. In fact, just like a home loan, paying a little more in the early years actually reduces the total amount customers pay over the life of the project.

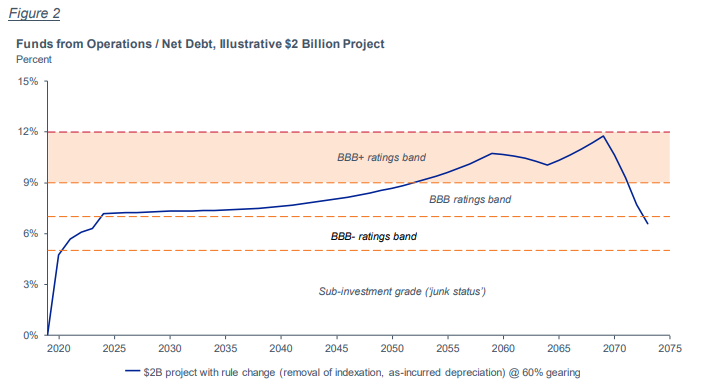

This change, together with a smaller change recognising costs when incurred in the early project life, would lift the Transgrid project from being consistent with investment grade benchmarks, towards achieving regulatory benchmarks by around 2050 (See Figure 2). This should enable the project to be financed cost-efficiently, reducing costs for customers.

Figure 2: Impact of proposed rule change – Projected funds from operation / net debt for illustrative $2b project (Source: Transgrid Submisson: National Electricity Rules change proposal –Making ISP projects financeable – Participant Derogation)

Similar approaches have been taken by regulators around the world, to recognise the specific needs of major new greenfields transmission investments. The New Zealand Commerce Commission recently approved comparable changes to enable the electricity transmission provider Transpower to go forward with required transmission investments.

Impact of the proposed change – the benefits of securing financeable outcomes

Making these changes to the rules is needed to ensure the delivery of the AEMO-identified priority projects consistent with the timelines set out in the Integrated System Plan. This would deliver system reliability, more access to market for renewable energy projects and greater wholesale market competition.

As an example of the benefits of addressing these issues, the Transgrid project identifies that Project Energy Connect is expected to save households in New South Wales about $60 per year in net terms if it proceeds. Applying the proposed rule to enable the project to be financed, in contrast, is estimated to result in just an additional $3 per household per year in the current regulatory period.

Similarly, households in South Australia are projected by ACIL Allen to save about $100 per year from lower wholesale prices, after meeting the increased transmission costs.

Where to from here?

The rule changes have been proposed to the AEMC as requiring urgent action, to provide for the timeframes in the actionable ISP to be met.

Over the past two years Australian energy market institutions, including the AER, AEMO and the AEMC, have invested significant efforts to develop and implement a revised set of regulatory tests and rules to underpin timely delivery of ISP projects. The Energy Security Board has been a key coordinating force in this work.

If the current framework does not support the practical financing of major new investments, much of the preparatory work clearing the way for efficient project commencement will be moot, raising some difficult long-term questions for achieving the integrated system plan.

This presents the regulatory regime with a ‘sliding doors’ moment, with two possible futures. Either way, financing the future grid may require changes ahead.