Unpacking the Energy Security Board Review: Does four into three go?

The review of the Energy Security Board (ESB) comes three years after it was established by the former Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Energy Council in 2017.

The ESB was tasked with shepherding through the implementation of the Finkel energy market review and providing a single coordinated point of advice for the COAG Energy Council.

The review, undertaken by former senior public servant Rhys Edwards, has examined the performance of the ESB around those two key tasks.

Making the job of the review more difficult was the failure of existing governance processes to lock in two foundational documents relating to the ESB – a ‘statement of expectations’ from the Energy Council, and a responding ‘statement of intent’.

Where formal expectations are unclear, assessment necessarily becomes challenging and to a degree subjective. The review positively notes the progress made in moving the Finkel recommendations forward and also cites progress on the many additional tasks given to the Board as an indicator of ongoing confidence in its capacities.

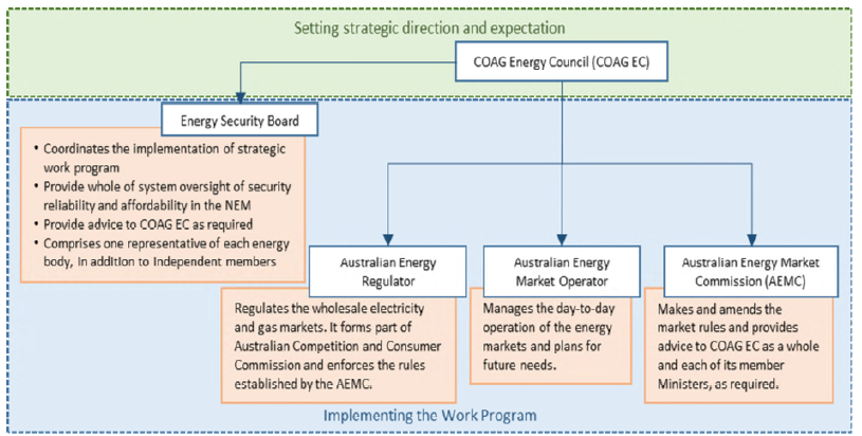

Part of the review was gathering significant stakeholder views on the real-world operation of the current energy market body architecture, and particularly the ESB’s place within it (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Roles and responsibilities of the market bodies Source: Review of the ESB, June 2020)

Generally, the feedback supported the view that, in the specific circumstances following the Finkel review, the ESB has been extremely well-led and played a valuable role in driving delivery of those recommendations; and that it has helped coordinate a range of complex market and policy changes associated with a rapidly transforming energy market.

Despite this, the review reports ‘little or no support’ for establishing the ESB as a continuing permanent body. The review notes:

This is perhaps not surprising, if you were starting Australian energy governance from a blank sheet of paper it seems highly improbable that you could come up with an institutional design that required four market bodies, particularly one where you separated out responsibility for energy policy advice.

Alongside recognition of a record of delivery, the review also heard of governance concerns from many stakeholders with the current ESB arrangements.

These include a continuing lack of clarity around its role and the follow-on potential for lack of accountability, concerns on transparency around special rule-making powers being exercised by a delegated but non-statutory body, and questions about the relationship between the ESB and other groups of senior energy officials.

The review proposes several solutions to these concerns.

First and foremost, it is recognised that the still outstanding foundational guiding documents such as statements of expectations and the associated statement intents from the bodies should be completed.

Three years after its inception, remarkably, these are not yet in place for the ESB. Similarly, the review recommends governments issue revised statements of expectations for the AEMC and AER and a revised statement of roles for AEMO, with consideration of AEMO’s role in the provision of policy or market development advice, a need first identified in the Vertigan governance review in 2015. The ESB review also observes that the role of the Board would be simplified by the removal of the extraordinary delegated rule-making powers assigned to it around reliability issues.

On the central question of the future of the ESB, however, the review proposes the Board should stay in existence until December 2021. Its role over this time will be critically linked to the completion of the initial ‘Post 2025’ review of energy market design.

Following this, it is recommended that part of the ESB’s work could be carried forward by a reconstituted Market Bodies Forum comprising the three existing market bodies – AER, AEMO & AEMC.

A key change in this regard is the potential move to a forum with simply three co-equal members, but no central coordinating body. The review also recommends a clear role and visibility of national energy officials in relation to this new body, observing:

Without diminishing in any way the excellent job the ESB has done, its existence has the potential for the ESB to “crowd out” Senior Energy Officials, and both Energy Ministers and Senior Energy Officials may find it perfectly convenient to have a mechanism like the ESB to push difficult (and sometimes intractable) policy problems onto. To resolve this, Senior Energy Officials will need to “step up” and become more connected to the work of the ESB.

The suggested way for this to occur is for the COAG Energy Council (or its replacement under the new National Cabinet format) to provide a national energy official to chair the Market Bodies Forum.

These recommendations, and others in the review, highlight that there is significant unfinished business in the energy market governance arena. A further example of this is the review emphasising the need for clarity on AEMO’s role as an ESB participant, particularly where policy choices are being considered which fundamentally impact on AEMO’s scope and its future functions.

Past Health of the NEM reports have described the objective of governments as ‘strong but agile’ governance. Overall, the review of ESB highlights that agility may be currently prevailing over strength, and the risks may now be more pressing than the ‘moderate’ assessment in this area in the current health-check.

The COAG Energy Council has responded to the review accepting many of its recommendations, though notably, it has not agreed to remove the ESB’s rule-making power. Those relating to governance issues have been identified for resolution in mid-2021.

For many, the Edwards Review will be welcomed as a thoughtful input into a critical debate. A careful assessment of effective and durable future governance options based on a clear view of market directions from 2025 is a long-overdue and an essential stepping stone to an energy future that delivers for all.