Is it time to retire network utilisation measures?

Utilisation measures have been referred to by various energy policy and regulatory bodies as well as public agencies throughout the years in different contexts. Often they are highlighted as providing some broad insights into either network efficiency or performance.

At its most fundamental, network utilisation measures how well a network’s assets have been used to meet maximum demand and have been used as a signpost as to whether network investments are delivering value for customers.

The most common utilisation measure is calculated as the very unpleasant phrase ‘non–coincident summated raw system annual maximum demand’. In English this means the peak of each zone substation’s highest demand at different times across the year without normalisation for temperature, divided by the total capacity of all zone substations on a network.

Other measurement variations include normalising for temperature or looking at the highest demand across a network throughout the year rather than at zone-substations.

Times have changed

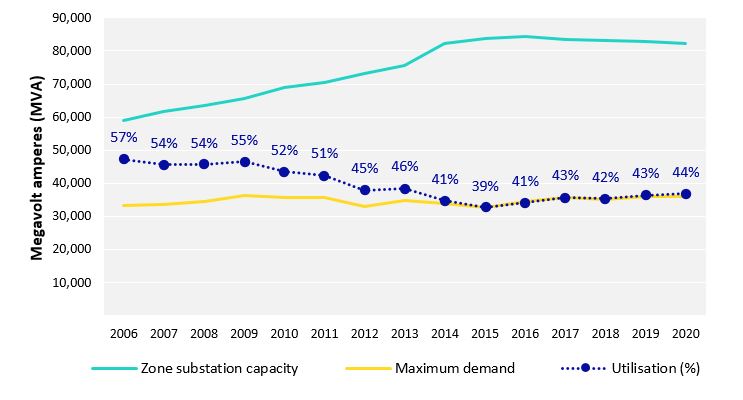

Network utilisation was traditionally very stable prior to the introduction of heightened state reliability targets. Previous overzealous targets in some cases drove additional network investment to mitigate against potential disaster on the most demanding days for the electricity network. These investments coincidentally resulted in some minimally-used capacity and a reduction in measures of network utilisation.

Figure 1 – Network utilisation of electricity distribution networks

Source: AER State of the Energy Market 2021, p. 168

In the years since, old State-based reliability targets have been wound back and Distributed Energy resources (DER) such as solar PV and battery uptake continues to surge. The measure of network utilisation has crept upwards as zone-substation capacity declined and distributors adapted to invest in new areas where it is now needed most, like high-growth suburban areas and DER-saturated parts of the network.

As DER continues to become a staple in the electricity system with customers seeking to lower bills and be environmentally savvy, its continued uptake is muddying the waters on what network utilisation measures actually show.

What do utilisation measures actually show?

Customers are demanding increased ability to export solar and connect their DER, creating local demand for network usage that may require additional network investment to facilitate. While DER might create network congestion at the local level, it can also result in a reduction in the overall demand requirement at the zone substation level.

This reduction in demand can have the effect of reducing utilisation measures, while also requiring additional investment in network reinforcement, raising questions about what these measures actually represent in a two-way energy system.

Whether fortunate or by design, utilisation measures most often cited are related to peak demand on each zone substation. This traditionally occurs in the evening when DER output is low and its impact on reducing utilisation is less severe, but still exists

In today’s electricity system, customers are showing strong preferences for DER uptake and distributors are rightly targeting investment to enable these preferences. Is it sensible then, that enabling customer preferences might be having unintended negative impacts on measures often associated with network performance?

This conundrum raises an interesting question about the usefulness of utilisation measures in a high-DER future, and whether we should be looking at alternatives.

Can we do better?

Discussing utilisation measures in the context of network performance may have made sense when we had single direction transmission ‘highways’ and large baseload generation centres, but much less so in a high-DER world with scattered, non-synchronous generation centres.

Network regulation in Australia doesn’t directly draw on utilisation measures for benchmarking or productivity assessment, and rightly so. It’s probably time to consider retiring utilisation measures and shifting focus to measures that have more meaning to customers in practice.

Perhaps something like the consumer facing output categories in OFGEM’s recent RIIO-2 framework[i].

[i] Page 22