Playing with gas – Victoria should substitute with its star performer

The Victorian Government recently announced an ambition to reduce emissions between 45 and 50 per cent by 2030[i]. This target will set the state on the path to reach net zero by 2050, a path that is increasingly well-trodden by states and territories choosing to go it alone in lieu of an overarching federal target.

Victoria’s Gas Substitution Roadmap seeks advice from stakeholders on the future role of the gas sector. So, why are we talking about substituting gas, what will we substitute it with and what does this mean for customers?

Natural gas, whether used by industry, business or households, or for supporting variable renewable generation, emits greenhouse gases and these emissions need to be reduced.

So – rather than simple a substitution – the roadmap is really about identifying options for cutting emissions associated with gas use, not necessarily moving away from all the benefits and amenity provided through the current natural gas supply chain.

Options to reduce emissions from natural gas use

A range of options exist to reduce emissions. These can be used individually, or jointly.

Figure 1: Reducing emissions from natural gas (source: Gas Vision 2050).

Improving energy efficiency in homes and businesses is the ideal way, and often first step, to reducing overall emissions and energy consumption. For example, a properly insulated home needs less fuel for heating, meaning lower emissions and cheaper bills.

Most major energy retailers are now offering packages where customers can pay a premium to offset the emissions created from their energy use. These packages can cover electricity use, gas use, travel or even the use of a motor vehicle.

All of Victoria reaching net-zero emissions will also require lower emission alternatives to natural gas.

Do we need to limit ourselves to one substitute?

Decarbonising natural gas or the electrification of the end services provided by natural gas can create zero emissions for Victoria. So, should the roadmap adopt one of these technologies? Or both?

Some advocates consider electrification as the only option. Their argument is that it is the cheaper and cleaner option and all that is required are massive subsidies to offset the capital purchase of the new appliances and 100 per cent renewables in the electricity grid. Victoria has a target of 50 per cent renewable generation by 2030, so a 100 per cent renewable grid is still some way off.

On the other hand, there is an argument that continuing to use gas infrastructure but decarbonising the fuel it provides is a better option. This is cheaper from a whole-of-economy perspective, it maximises the utilisation of existing gas and electricity networks and retains the option for customers to use a gas-type fuel – it would just be a renewable one.

Two different pathways can deliver decarbonised gas. One being the use of hydrogen, which when burnt does not produce greenhouse gases, and the other being based on the use of renewable methane, which also does not contribute towards global warming as the carbon dioxide produced when burnt simply replaces the carbon dioxide the renewable fuel absorbed when it was created.

Rapid electrification increases costs and emissions

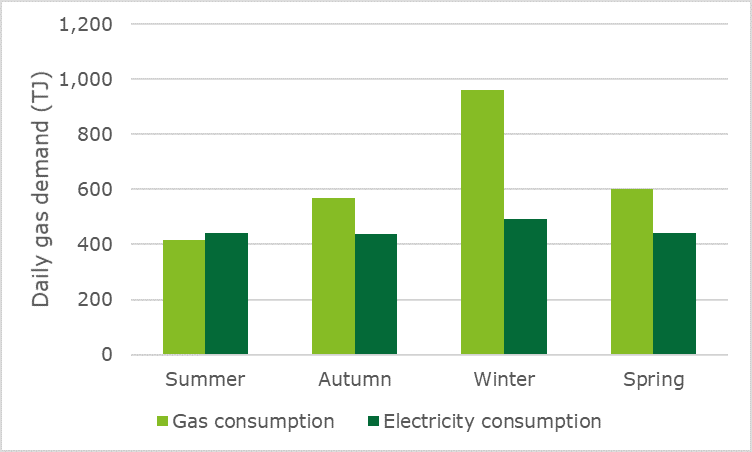

In households, natural gas is used to provide heating services in the forms of cooking, hot water and space heating. Not much of the latter is required in summer, obviously, but massive amounts are used in winter. For Victoria, the daily natural gas consumption increases from 417 TJ a day in summer[ii] to 971 TJ a day in winter. More than double the summer load is needed to provide heating in winter – to the two million households that choose to be connected to gas. The gas storage, transmission and distribution infrastructure enables this doubling in gas demand to be met. Daily electricity consumption varies slightly throughout the year with more electricity consumed in winter compared to summer[iii].

Figure 2: Daily gas and electricity consumption in Victoria (Source: Energy Networks Australia analysis, AEMO data)

Electrifying the gas load would require additional electricity generation, transmission, distribution and a replacement of appliances. Building the electricity system to accommodate the winter peak for heating would result in that system being under utilised for much of the year. This is not an efficient way to invest.

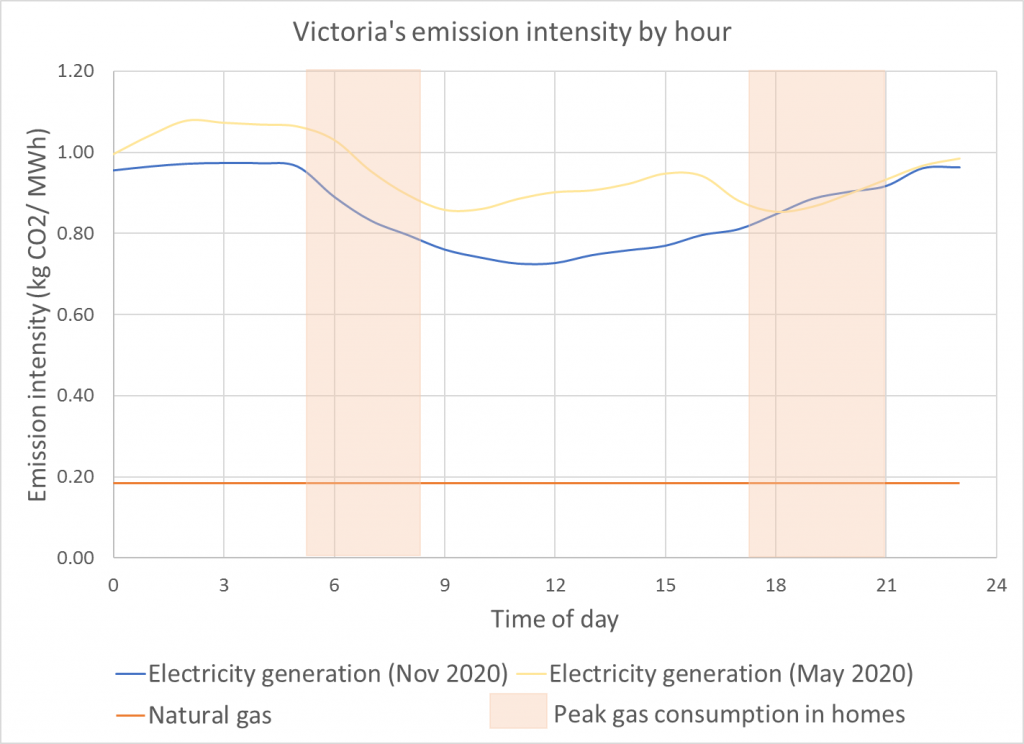

Electrifying the gas load before reaching zero emissions from electricity may also increase emissions. Victorian electricity generation is still predominantly emissions-rich brown coal – and will be so for some time.

When heating is required – during the morning and evening periods in winter – it coincides with lower levels of renewable generation so more of the electricity is supplied by brown coal. This emission intensity is between four and five times that from using gas directly. While heat pumps offer higher theoretical efficiencies, these efficiencies reduce at those colder temperatures. In short, the stated benefits of heat pumps fall away when they are needed most resulting in increased emissions from electrifying gas demand.

Figure 3: Emission intensity of gas and electricity in Victoria (Source: Energy Networks Australia analysis, AEMO data)

Decarbonising the fuel results in lower bills

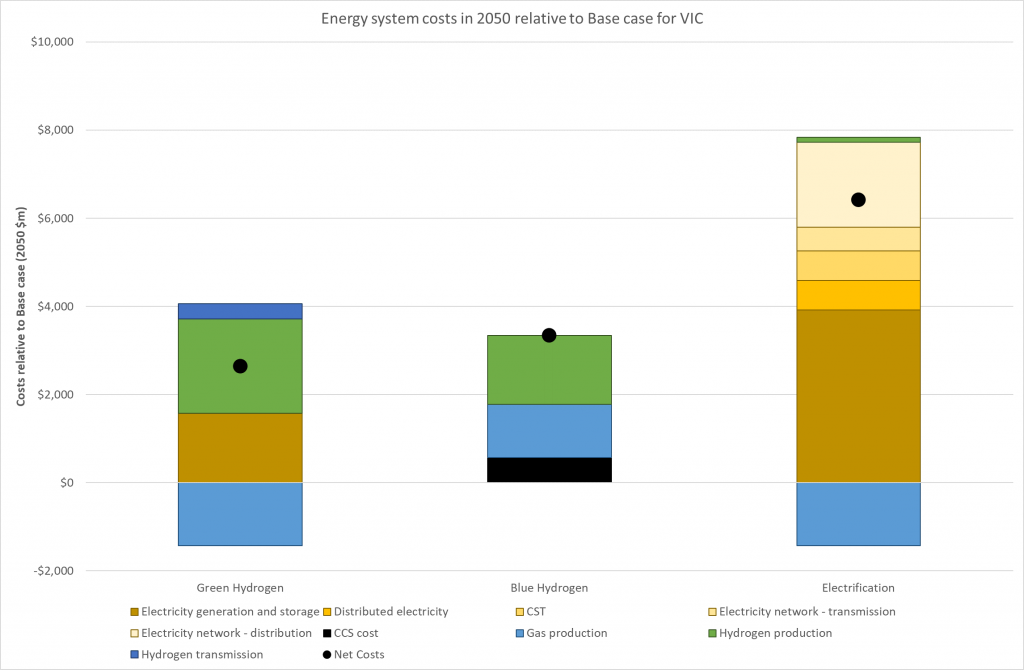

Replacing natural gas with a decarbonised fuel is a better way, and costs less than half the electrification option.

Appliance upgrades would be needed for the electrification scenario or when converting to 100 per cent hydrogen, but the ongoing systems costs are what will drive customer bills.

Producing hydrogen comes at an extra cost compared with natural gas but this is still much less than the additional infrastructure required from a full electrification approach. The differences are mainly related to the value of the gas supply chain to be able to store vast amounts of energy, which essentially reduces the amount of renewable generation capacity that is required.

Re-utilising the existing gas distribution network with hydrogen or renewable methane also avoids the unnecessary costs of upgrading the electricity distribution network to deliver that additional electricity to businesses and households. Full electrification also needs a hydrogen supply as industrial feedstock and to provide very high temperature fuel to industry.

Figure 4: Comparison of renewable gas and electrification systems costs for Victoria (Source: Gas Vision 2050)

There are a range of options available to achieve net zero emission for Victoria. The renewable gas option will get the state to the same emission result as an electrification pathway, but at $3 billion a year less. That’s $3 billion less out of customer pockets.

The right to substitute and the right substitute

Customers already can choose whether they use gas or electricity for their home heating, and they also have a range of options available to reduce their emissions.

Achieving state-based emission targets should enable customers to switch to new energy sources. This may require switching from natural gas to a different fuel, whether that is renewable gas or electrification. The choices made by customers should not be limited to higher emitting and more expensive energy options but reflect their personal preferences and the best substitute on offer.

[i] https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/climate-plan-cut-emissions-and-create-jobs

[ii] This use is mainly for commercial and industrial and power generation

[iii] The 30-minute electricity peak in Victoria occurs in summer but the total average daily consumption in winter is higher compared to summer.