Are we ready for the EV revolution?

A recent State of Electric Vehicles report by the Electric Vehicle Council indicated that electric vehicle (EV) sales in Australia have tripled in 2021. This increase represents a two per cent market share of all sales, compared with 0.78 per cent in 2020. The question is, are distribution networks ready for the EV uptake?

In our previous article Electric vehicles and the grid – can we just plug and play?, we presented some of the potential impacts of EVs on distribution networks, which included asset congestion, voltage issues, conductors and transformers overload. In this article, we look at the results from the University of Melbourne’s EV Management and Time-of-Use Tariffs report which explores possible approaches to mitigate impacts from residential EV chargers on distribution networks. The report is part of the collaborative EV Integration project between Energy Networks Australia, University of Melbourne, the Centre for New Energy Technologies, and the Australian Power Institute.

This report investigates the effectiveness of EV management strategy and time of use (ToU). Selected rural and urban feeders (powerlines) for NSW, Tasmania and Victoria were considered in the study. It should be noted that the results presented apply to those feeders only, not the whole distribution network.

EV management strategy

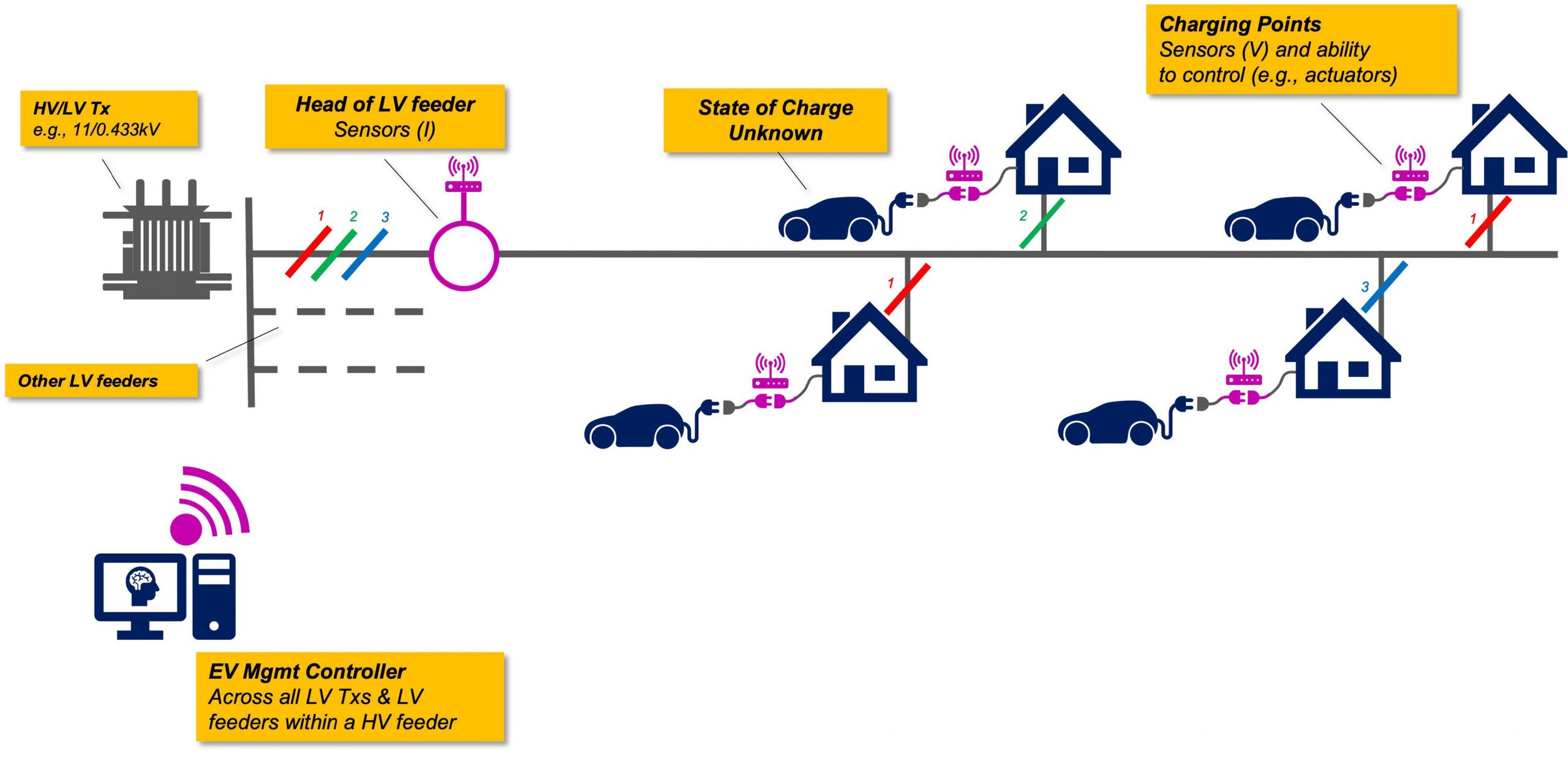

There are a range of EV charging management strategies. This study utilised direct management of chargers, given it did not require models of low voltage (LV) feeders which are not readily available for most distribution network service providers (DNSPs). Sensors were installed on certain locations on the feeder to measure and monitor thermal and voltage changes. When the sensors detected changes outside optimal operating limits, a signal was sent to the EV chargers to connect or disconnect.

Figure 1 shows the architecture of the proposed management strategy.

Figure 1: Architecture of EV Management Strategy

The report is not recommending which entity should manage these chargers, but rather aims to investigate the effectiveness of EV management strategies in terms of the impacts on customers and networks.

Some of high-level findings detailed in the report:

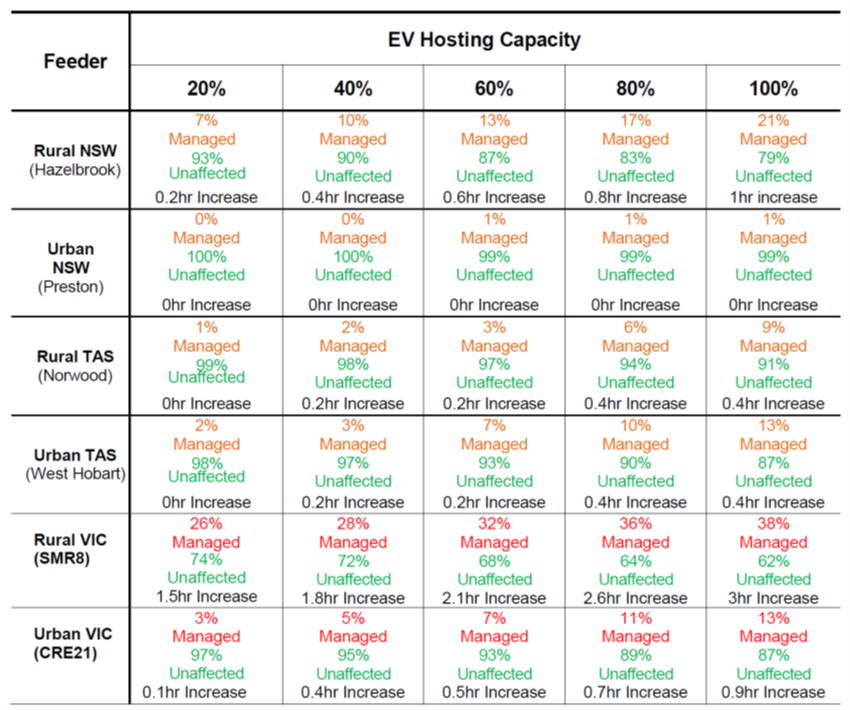

- Number of impacted customers: Most EV customers were not impacted by the EV management strategy. Even for the worst performing feeder (rural VIC), 62 per cent of customers were not impacted at 100 per cent EV penetration (100 per cent penetration means all residential customers connected to the feeder have EVs)

- Charging time: Implementing the direct EV management strategy could increase the charging time by maximum of three hours, while the average time increase was 1 hour. In a small number of cases, the charging time was increased by more than three hours.

- Location: Customers in urban areas were found to be much less likely to be impacted by higher EV penetration compared with customers in rural area. Rural areas required much more significant management (e.g., approximately 38 per cent of customers were impacted in the rural VIC feeder considered in this study).

- Hosting capacity: The findings show that a two to four-times increase in hosting capacity could be achieved with acceptable impacts (delays) to customers, as the EVs would still be charged by the morning.

The table below presents a summary of the impact on customers across the investigated feeders from 20 per cent to 100 per cent EV hosting capacity. The table can be read as: (for example) Rural NSW at 20 per cent hosting capacity – seven per cent of EV chargers are managed and 93 per cent of customers are not affected with an increased charging time of 0.2 hours per EV customer.

Table 1: Summary of the impact of customers across the investigated feeders

Time-of-use tariffs

ToU tariffs can be used to incentivise customers to shift their charging time to off peak periods. The ToU strategy investigated in this study aimed to understand the rate of customer adoption of ToU to the EV hosting capacity, i.e., how many customers needed to adopt TOU to reduce network issues.

Some of the high-level findings detailed in the report:

- ToU adoption rate vs EV hosting capacity: If 20 to 40 per cent customers are on ToU tariff, the EV hosting capacity can be increased by 20 per cent.

- ToU tariffs might not be enough on their own: In some congested feeders, the ToU tariffs need to be combined with an additional solution, e.g. an EV management strategy.

- Additional benefits beyond increasing hosting capacity: Generally higher adoption of ToU tariffs reduce the magnitude of asset congestion, which means less investment is needed to manage these issues. This could provide a better value-for-money return for customers and DNSPs.

The main take away from the study is that implementing an EV management strategy could help increase EV hosting capacity and reduce network issues. Combining EV management with ToU tariffs can maximise these benefits and save customers money in bills by increasing network utilisation and reducing the need for investment.

Generally, such solutions can be considered for a short or medium term given that they do not require detailed models of LV networks and significant asset replacement or augmentation. These solutions may be applicable for long term if modified and combined with other approaches to form a complete solution.

The full report is provided here.

Other project related materials are provided on our ENA website, University of Melbourne project page and C4NET project page.