Berlin Energy Dispatch #2 – the social compact for energy infrastructure

When you travel around Germany you almost don’t notice the role energy networks play. This is because, in contrast with Australia, most of the infrastructure is out of sight and out of mind. But there is a cost to this. Despite vastly different population densities, Australians and Germans pay about the same for their electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure. It is clear there is a different social compact around what we are willing to pay for. Achieving this balance between the cost of delivering new infrastructure and the community and environmental impact is the role of planning and investment frameworks. Nowhere is this more relevant than the current challenge of building new transmission infrastructure to facilitate the transition to net-zero.

This is the second article in a series reflecting on a recent delegation of Australian energy experts to Germany. The first article focused on the big picture. This article focuses on network structure and efficiency, with a case study on transmission planning and investment. The next articles will focus on distributed energy resources and innovation, and the electrification and gas discussion.

Transmission and distribution structure and cost

The German electricity transmission and distribution systems are very different to Australia’s. There are four transmission system operators (TSOs) and 872 distribution system operators (DSOs) in Germany. Many of the DSOs also manage reticulated heating, gas and water distribution networks. The TSOs are privately held, while most DSOs are publicly owned and quite small, with 70 per cent having less than 30,000 connections. Only ten per cent of German DSOs have more than 100,000 connections.

By contrast, there are five transmission businesses and nine distribution businesses in the National Electricity Market (NEM) in Australia. On average distribution businesses in the NEM have far more connections than German DSOs. For example, one of our smallest distribution networks, TasNetworks, has almost 300,000 residential and business connections.

One of the biggest differences appears to be in the physical characteristics of the networks. The German networks are much stronger and more enmeshed at both high and low voltage. Furthermore, most large-scale renewable generation connects into the distribution system in Germany, whereas in Australia it is transmission connected.

In 2021 Germans paid about 13 Australian cents per kWh for their transmission and distribution networks.[1] Australians paid about the same (for their transmission and distribution networks).[2] It is staggering that Australian network businesses have been able to deliver safe, secure and reliable energy across a vast geographical area at around the same cost as delivering the same service in a densely populated European country. While the circumstances aren’t exactly comparable given the slightly different roles networks play in each country (for example many of the functions Australia’s independent market operator fulfils are undertaken by the TSOs in Germany) the outcome is still revealing.

Networks and values

When you are in Berlin it is literally impossible to see the reason why, despite vastly different population density, the network cost outcomes are so similar. This is because all the distribution power infrastructure is underground. Even as you travel out of the city or search the small towns on google street view, the only energy infrastructure you can see are wind farms, solar arrays on rooftops and some transmission lines.

In Australia power infrastructure is only underground in the heart of major cities. Everywhere else distribution poles and wires – which are far cheaper than undergrounding – criss-cross neighbourhoods and transmission poles and wires traverse the countryside. When you introduce yourself in Germany as representing all the Australian electricity ‘poles and wires’ businesses there are blank stares, some crickets, and then you realise you must rephrase to use relatable language.

To keep energy costs competitive and services reliable we build and maintain our energy infrastructure as cheaply as possible. This is one of the great successes of Australia’s incentive based economic regulatory framework for its electricity network infrastructure. This is broadly the same regulatory approach taken in Germany. However, in Germany there appears to be both a social acceptance of the costs of undergrounding power infrastructure as well as an engineering led culture to build infrastructure that is robust well into the future, rather than an economist led culture of building incrementally and cheaply.

The transmission case study

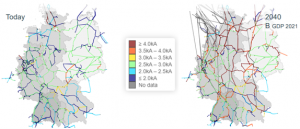

This is playing out in the transmission sector in Germany. To meet its net zero goals, significant new transmission is required to transport wind energy in the North of Germany to the industrial load centres in the South and West. The grid strengthening required between now and 2040 was highlighted in a presentation from 50 Hertz, one of the four German TSOs.

Figure 1 – grid strengthening requirements to 2040

[Source: 50 Hertz, September 2022]

In Germany there are some similarities to the transmission planning and investment frameworks we have here. The TSOs develop 15-year transmission development plans under scenario-based models (much like our Integrated System Plan) which are then signed off by the ministry. Once signed off, the projects must be built. The development plans are the main opportunity for public engagement on transmission planning. There does not appear to be an equivalent further test of options to meet the identified need to increase transfer capacity, such as the NEM’s regulatory investment test for transmission (RIT-T).

While this planning and investment process appears on its face to be quicker than the process in the NEM, it is often held up significantly in legal challenges relating to environment and planning issues. Community and environmental challenges have led to major delays to and variations of projects. For example, one development has only just started construction after taking more than 15 years to work through legal challenges. Other major projects transferring power through the middle of Germany on high voltage direct current (HVDC) lines will be underground for almost half of the overall distance, at around three-times the cost of above-ground transmission.

Whether in Germany or Australia, customers and communities should be included in the process so that social license and community support is balanced with costs borne by energy consumers. The planning and investment frameworks should help efficiently navigate towards a shared position that is in line with what customers and communities are willing to accept. The compromises struck are clearly different in Australia and Germany, but there are lessons to be learnt in the effectiveness of the processes in finding the right balance.

With energy reform in the NEM, we can usually point to a current process looking at similar questions in a ‘here’s one we prepared earlier’ fashion. This issue is no exception, with stage three of the Australian Energy Market Commission’s transmission planning and investment review consulting on the balance between timely and efficient investment in major transmission infrastructure. We look forward to engaging and getting the balance right for Australian communities and electricity customers.

[1] See network charges, metering charges and various network related levies and surcharges, which together make up just over 25 per cent of a retail price of just over 32 euro cents per kWh – https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/EN/RulingChambers/Chamber8/RC8_06_Network%20charges/RC8_06_Network%20charges.html

[2] See https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/cost-of-supplying-electricity-to-households-at-an-eight-year-low