Powerful neighbours from the good people in power

Some say good fences make good neighbours, however there are some newcomers moving into streets across Melbourne that you might just want to be close to.

These new kids on the block are neighbourhood batteries – and a feasibility study from Victorian energy distributors CitiPower and Powercor is showing how they can become valuable community assets. A powerful neighbour that you’ll want to have nearby.

The new kid on the block

Neighbourhood batteries are new types of electrical assets that have only really started to be introduced in Australia since 2020.

Neighbourhood batteries can either sit on existing power poles or on the ground in an unobtrusive area of the community, often on the land of a participating local council or organisation.

They are connected directly to the low voltage electricity distribution network and range in size from 30 kilowatts to five megawatt capacity. They are charged by either electricity sourced from large-scale generation or from local rooftop solar exports. The batteries provide benefits to a defined local community that is directly serviced by the section of the network where the battery is located.

The neighbourhood batteries have the dual advantage of providing support to the electricity network by soaking up excess solar production and providing clean, cheap energy to the community in which it is produced when demand is high.

Another key benefit of neighbourhood batteries is they offer all people within a community the opportunity to participate in the clean energy future whether they have solar panels on their roof or not. In the transition of the electricity market to more renewable energy, customer take up of rooftop solar has soared. However, not all customers are able or willing to install their own system – due to financial reasons, not having a suitable roof or because they live in apartments or rental properties.

Fig1. ‘The benefits of batteries’ CitiPower and Powercor

Time to the meet the neighbours

In 2021, CitiPower and Powercor received funding from the Victorian Government’s Neighbourhood Battery Initiative to lead a feasibility study into community batteries, working with another distribution network, United Energy, 12 councils and community energy and greenhouse alliances.

The Electric Avenue Feasibility Study scanned regions across 65 per cent of Victoria to identify 30 preferred locations for neighbourhood batteries and in the process, identified insights into their location, design and planning that could benefit future projects.

The study found the chief benefits anticipated from neighbourhood batteries were in helping to enable and keep locally generated solar energy local, supporting high power reliability, generating income from wholesale energy trading or contributing to energy resilience.

Of the 30 preferred locations for neighbourhood batteries identified, 17 have the potential to be feasible based on their ability to address electricity distribution constraints and service more than 6,000 customers. Study partners identified 13 sites that could support community objectives.

Fig 2. Various project models for neighbourhood batteries

Peeking through the curtains

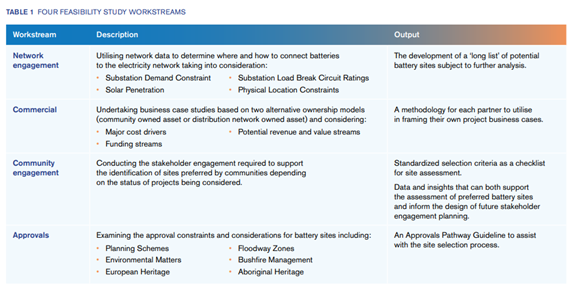

In less than 12 months, CitiPower and Powercor worked with local councils and community organisations to investigate the various uses for batteries, the key factors to consider in their location, design and planning, and how they may potentially create revenue for communities. The collaboration sought to define a replicable, systematic process for developing the business case for neighbourhood batteries. Four distinct workstreams were developed under the study with clear outputs to assist in measuring the feasibility of the battery.

The Electric Avenue Feasibility Study was successful in identifying a large number of potential sites for neighbourhood batteries potentially benefitting multiple communities. And although CitiPower and Powercor successfully created a consistent framework in which to measure the feasibility of a neighbourhood battery, the study recognised that neighbourhood battery projects are not easily scalable and the models not necessarily transferable to new neighbourhoods. They are highly contextual. A model for a community battery that is working in Yackandandah in regional Victoria will not translate to inner city Melbourne, for example.

Most people have some awareness of big grid-scale batteries and household batteries. CPPC’s Electric Avenue project lands in the mid range between these two types of storage devices. It is a great example of how distribution networks are innovating to support customers and provide a more secure and reliable grid as we integrate more renewables into our electricity system.