Why everyone in the UK is watching The Bill

Increases in energy supply charges across the UK are cause for concern as almost 22 million households will see an average increase on their energy bill of 54 per cent from April 2022. For the average British household that equates to about £693 a year.

Largely, the increase is driven by a rise in global gas prices over the past six months. Notably it is also winter in the northern hemisphere. Internationally, wholesale gas prices have quadrupled in the last year due to a colder than average winter putting pressure on demand, a fairly windless few months across Europe which has meant a lack of dispatchable renewable wind power – linked to a phenomenon known as dunkleflaute – and increased demand from China.

It would seem the butterfly effect is in full flight.

Given about 85 per cent of British homes reply on gas central heating and gas generates a third of the county’s electricity, the UK is harder hit than most.

But why such a dramatic spike at the bottom of the bill?

Enter the price cap.

What’s behind these increases

The energy price cap will increase from 1 April, allowing retailers to pass on their incurred costs.

When global wholesale gas prices spiked, many smaller energy retailers collapsed. This was largely caused by the energy price cap that prevented energy businesses from passing on increased costs to consumers. Larger, more established and diversified retailers were able to absorb the increase for a longer period of time.

The price cap is updated twice a year and tracks wholesale energy and other costs.

It stops energy companies from making excessive profits, ensuring customers pay no more than a fair price for their energy.

The price cap eventually allows energy companies to pass on all reasonable costs to customers, including increases in the cost of buying gas.

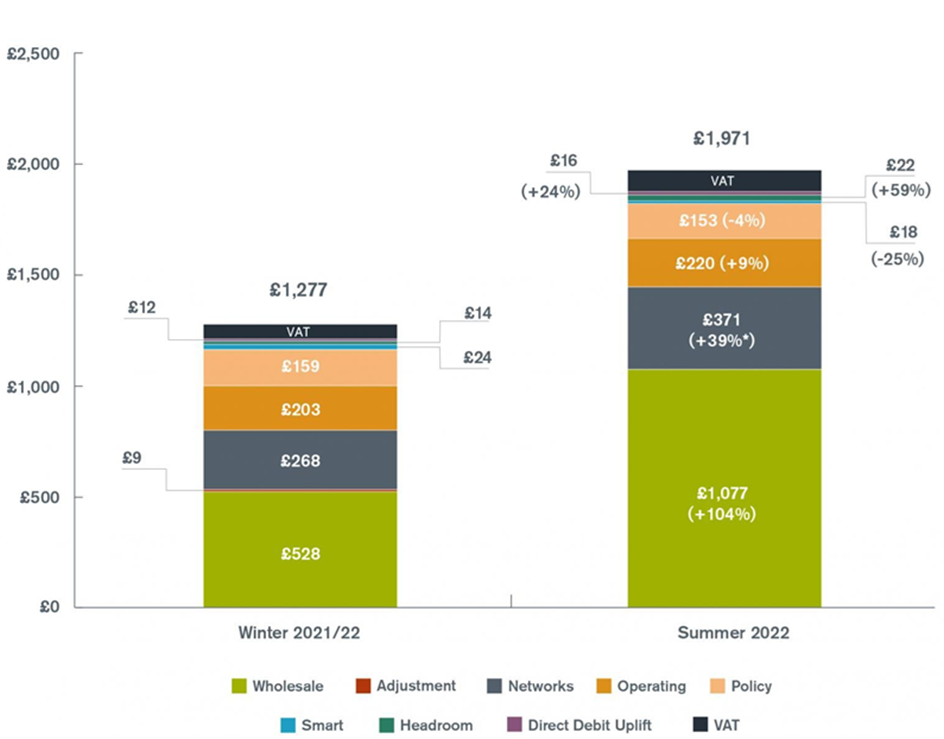

The below graph shows the breakdown of costs within the energy price cap. You can see the more than doubling of the wholesale charge between winter 21/22 and summer 2022.

There is also a sizeable increase in network charges within the energy price cap. The main driver of this increase is not really a network cost at all. It’s a huge increase in the the Supplier of Last Resort (SoLR) levy (£68) which is used to fund the costs of larger retailers having to take on customers following the collapse of smaller retailers.

Under the price cap mechanism, energy companies will be allowed to pass on these higher costs from April 2022 when the new level takes effect.

Since the price cap was last updated in August by the regulator, Ofgem, the current level does not reflect the unprecedented record rise in energy prices which has since taken place.

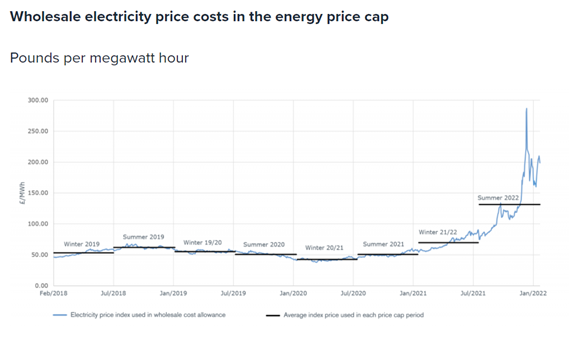

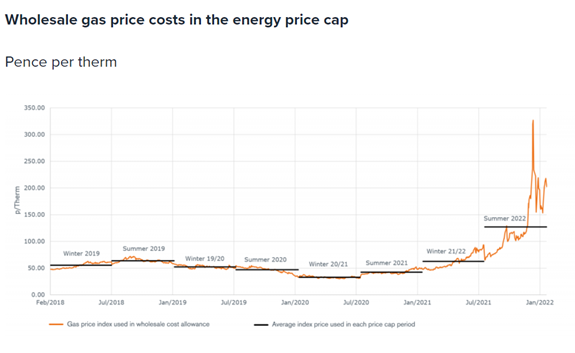

The below graphs show how wholesale gas and electricity prices have dramatically jumped between July 2021 and January 2022.

What’s been the reaction

Energy policy and politics make strange bedfellows. Most politicians would prefer it off the political agenda all together. It involves complicated algorithms that often include factors out of anyone’s control, it’s highly regulated which means blame can be placed squarely at the feet of the current day’s government and it’s hard to explain to the average punter.

On the flip side, bill relief packages are easy to institute, are palatable to the public and are easy to explain – “You have a bill of £X and the government is going to knock £Y off the bottom of it.”

This is the general premise behind the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak’s bill relief package to help ‘take the sting’ out of the bill rise.

Sunak is also a favourite for the Conservative leadership which could see him Prime Minister soon.

Under the support plan, £350 will be offered to households with £150 deducted from the bill. The remaining £200 will be taken off energy bills but households will need to pay it back over instalments from 2023.

For most households this still means an annual increase of around £400.

Business is probably more nervous. Raw from the past two years of COVID shutdowns, lockdowns, restrictions and a contracting economy, businesses are already dealing with slim profit margins .

Soaring energy prices will mean the costs will again be passed onto customers, with some high-use businesses owners weighing up the merits of using diesel generators rather than buying directly from the grid. Ironically, some of these businesses have been the recipients of government grants to help them adopt a greener business model.

It is a sad state of affairs for a nation trying to lead the rest of the world on adopting net-zero targets.

A cautionary tale…

Already the UK has pulled the ‘price cap’ policy lever – which seems like a good idea. It makes sense to a family with a limited household budget to stop big, greedy energy companies charging carte blanche what they will for power.

But it leaves little to no room for error, such as an increase in demand or in the event the wind doesn’t blow as hard, or the sun doesn’t shine as brightly.

Another key issue is energy security. A key reason for the hike in gas prices has been supply concerns and these have only increased in recent weeks with the threat of war in the Ukraine. No government wants their energy security to be dependent on Vladimir Putin, but much of Europe is squarely in that camp.

As a major energy exporter Australia has less energy security concerns, indeed the transition to electric vehicles is a key opportunity to reduce our reliance on petroleum imports.

The lesson in all of this could be that political market interference of the magnitude playing out in the UK is seldom a good idea. Allowing flexibly within the price caps could be the answer to the UK’s problems. Allowing the cap to increase marginally more often to reflect the true cost of wholesale energy without the bill shock would at least be more palatable to customers. The invisible hand of the market may also right itself and there will be a natural evening out of the peaks and troughs.

While similar drama appears very unlikely to play out in Australia anytime soon, the problems in the UK should serve as a cautionary tale from the butterfly who flapped too hard.