BCG Report: A whole-of-system opportunity

This week, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) released a new report that focuses on the phases needed to support Australia’s energy transition at the “ least cost and in the most robust manner”.

The report demonstrates a lot of things about the phases of the energy transition, but an obvious takeaway is the gas versus electricity in homes debate is the wrong one to have.

Electrification and the role of gas in our energy supply stir up fact based, and emotive, views from both sides. But unfortunately, the debate has missed the opportunity to delve into what proper decarbonisation of our energy economy is really going to need.

How do we transition to net zero at least cost and benefits the climate, customers, and communities?

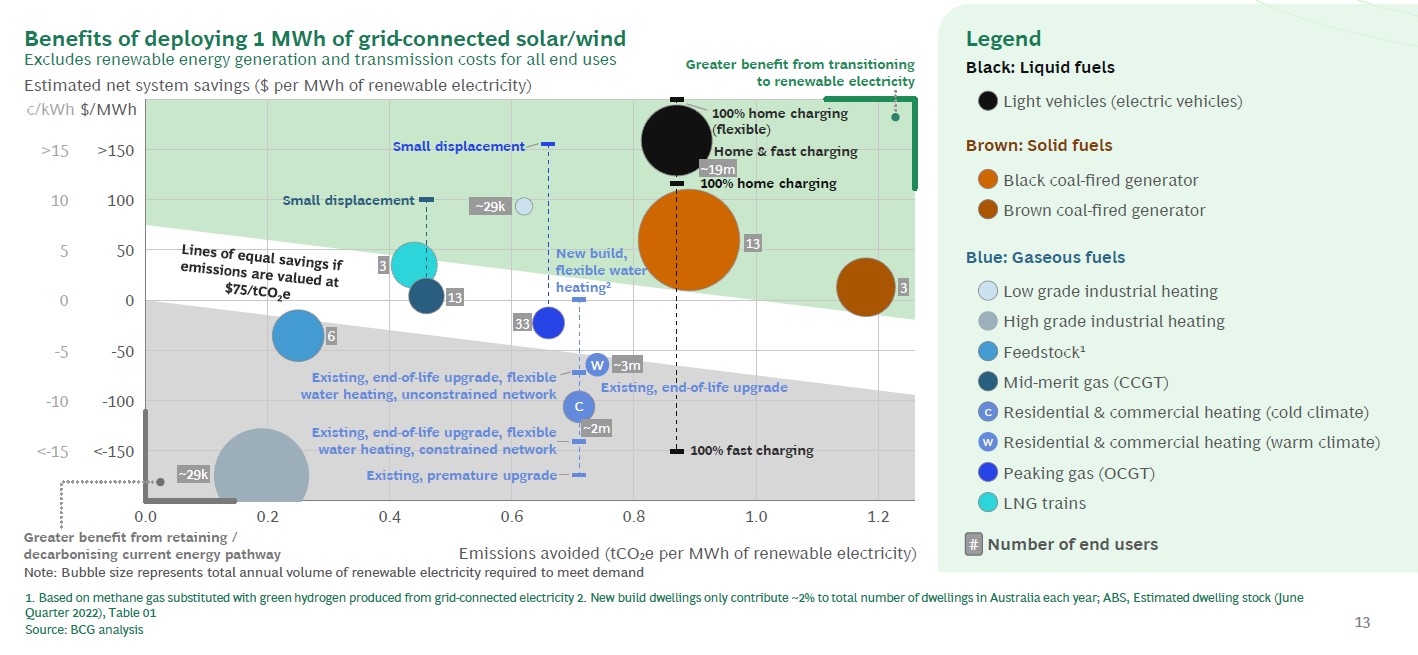

What stands out in the report is there are three big ticket items that will make a proper dent in our emissions – the removal of coal from the system; the electrification of light vehicles; and the next biggest? Addressing the emissions of industry for which electrification isn’t an easy option.

As one generation ends, another begins

The removal of coal in Australia’s energy mix has been a long time coming. As coal fired power plants have reached the end of their life, there has been a significant political, societal, and environmental shift away from our biggest polluter.

Coal is being replaced with large scale wind and solar farms, supported by storage solutions – think community batteries and grid-scale batteries. Most people in the industry know this hasn’t been an easy ride. In fact, it’s been more like a roller coaster.

When the smokestacks that dot the horizon in the Latrobe Valley were built, power generally ran in one direction. Power was generated using brown and black coal, it travelled through some high voltage wires and transmission lines, was converted into low voltage and then into homes and businesses.

Nowadays power still runs in the traditional way but can also run from where power is generated, such as in homes from solar panels and then fed back into the grid. If not managed correctly this can cause all sorts of congestion on the grid. (Imagine driving the wrong way down a three-lane highway).

Coal was our safe, reliable and stable power source for more than 100 years. It served us well, but it’s time to move on to a newer and cleaner option.

Steering towards EV’s

Transport is responsible for approximately 18 per cent of emissions in Australia. Passenger vehicles contribute a significant amount of that emissions output. Increasing EV uptake is the most effective way to decarbonise and reduce emissions in the short-to-medium term.

Electricity networks are already working at pace to ensure they are best placed to manage the demands that will come with increased EVs relying on the grid. They are investing in the network to ensure it is stable and reliable enough to handle an increase in demand.

Now, if we can get the right policy settings in place, there is an opportunity for EVs to actually help manage the increased amount of rooftop solar entering the grid by drawing the energy out when it’s at peak and in turn, decarbonise the energy system faster and help customers reduce their household energy bills.

There is more to be done in this space, including equitable access to charging infrastructure to ensure we are ready to meet the demand. If we can charge at reasonable prices with infrastructure close to the home, we have at our disposal one of the best levers to reduce emissions at lowest cost.

Manufacturing cannot be left behind

The report supports the Grattan Institute’s analysis that gas emissions are responsible for 22 per cent of the total emissions in Australia. What has been absent from the debate so far is a clear decarbonisation pathway for industrial feedstock and high-grade industrial heating, where the technology to electrify doesn’t exist or is prohibitively expensive

This is where we need to target our efforts. If we do not find viable pathways to decarbonise these processes – critical for the manufacturing of things like fertilizer and cement – we are not just risking our ability to reach climate targets; we are putting at risk Australian products and industries that are core components of our economy.

This may not feel like a big problem today, but what does the future look like without a viable alternative for this hard to abate part of economy? For example, how will Australia build homes without a brick or cement industry?

Natural gas will not be here for ever, it must come to an end, but the industrial sector that relies on it needs viable alternatives. Hydrogen and other renewable gases offer those alternatives.

By exploring how to bring in renewable gas like hydrogen and biomethane, manufacturing industries across Australia do not have to wake up in 10 years and be told they can no longer be part of the economy.

The question is what is the role of gas network infrastructure in bringing forward renewable gas for these hard to abate parts of the economy? Investments are already underway. Projects like HyP SA – where a hydrogen blend is servicing a suburb of more than 4,000 homes in a “hydrogen hub” and forming an anchor to industry to source renewable gas for which they have no alternative.

Our economy cannot survive without heavy industry, but as it stands our net zero targets can’t be reached with them. Let’s make sure we, as the sector, are looking at the whole picture.

Taking stock of the whole system

The BCG report signals the need for a whole-of-system look at where to prioritise our attention and our investment so that we can support communities to reach net zero.

To effectively consider the whole picture we need acknowledge the vital role of infrastructure in the transition and avoid policy missteps that can lead to imbalanced focus and misguided priorities. The path isn’t simply about an either-or discourse but is about how all the pieces fit together to make the biggest impact.

If we do not develop viable pathways to help decarbonise the areas that currently cannot be electrified, then we will ultimately limit our capacity to reach net zero.

[1] https://www.ntc.gov.au/light-vehicle-emissions-intensity-australia#takeaways

Feature Image: Cement Kiln Burner