What do pork knuckles, beer and hydrogen have in common?

Many Germans enjoy pork knuckles, pretzels and beers during Oktoberfest. This is a celebration to commemorate the marriage of Prince Ludwig’s to Princess Therese von Sachsen-Hildburghausen in Munich in 1810[1] and is celebrated in many countries around the world.

Undoubtedly, Germany is one of the world’s leading consumers of pork knuckles and beer during this celebration. Similarly, with its ambitious hydrogen targets, Germany is likely to become one of the world’s largest consumers of hydrogen. Let’s take a look at some recent developments.

Germany’s hydrogen demand

Germany is one of the leading countries to adopt clean hydrogen in its future energy mix. The German Government expects its demand for clean hydrogen and hydrogen derivatives to reach between 320 and 500 PJ[2] by 2030[3]. Around 50 to 70 per cent of that will have to be imported.

To put this into context, according to the Hydrogen Council, projects around the world that have reached Final Investment Decision will deliver around 550 PJ[4] of hydrogen by 2030 with the capacity evenly split between low carbon and renewable hydrogen[5]. The Hydrogen Council estimates that a number of additional projects will reach FID in the coming years and the likely production of clean hydrogen by 2030 will be in the region of 1,400PJ and 2,160PJ. What’s clear is that the demand for Germany is a major proportion of anticipated global production.

Germany is bullish about hydrogen as it has essentially legislated other energy options out. For example:

- Germany’s coal exit plan aims to phase out coal by 2038[6]. Germany had around 38 GW of coal fired power stations and planned to reduce this to 17 GW by 2030 with a complete phase out by 2038. Some states are planning a complete coal phase out by 2030.

- Germany has also phased out nuclear power with the last three nuclear reactors shut down in 2023[7].

- Germany is working to reduce its reliance on imported natural gas from Russia.

- Germany banned using carbon capture and storage (CCS), although it seems that recent developments are allowing the use of CCS in offshore regions[8] for sectors that are difficult or impossible to abate. The CO2 emissions from producing cement[9] are an example of very difficult to abate.

Combined with that, Germany has ambitious emission reduction targets of at least 65 percent by 2030 and 88 percent by 2040. To contribute to this, Germany continues to build large scale wind and solar plants across the country. Renewables will meet part of its current electricity demand, but heat, mobility and industrial energy demand need further sources of supply.

Figure 1: A wind farm in central Germany.

Hydrogen infrastructure

To deliver hydrogen), Europe has planned a hydrogen backbone drawing on a range of import options. Imports corridors come from North Africa via Italy, or from the west via Portugal and Spain, or from Finland in the north or via the North Sea.

Figure 2: Schematic of European hydrogen import corridors (Source: Germany’s hydrogen import strategy)

This Hydrogen backbone will deliver 31,500 km of transmission pipelines with expected commissioning by 2030[10]. It is expected that, between 2030 and 2050, this initiative will save €330 bn compared to a model where hydrogen is produced in local clusters.

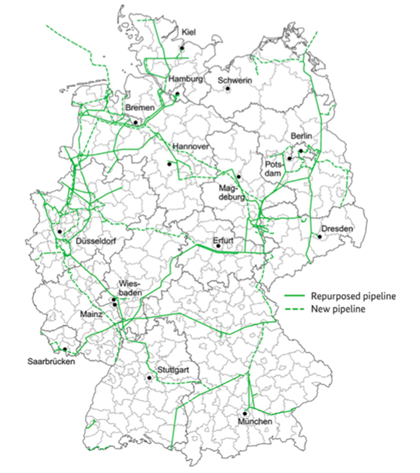

Germany is in the centre of this cluster and has its own detailed plans for the infrastructure[11]. The core network will be around 9,700 km in length and be built between 2025 and 2032. It consists of 40 per cent new pipelines and 60 per cent repurposed natural gas pipelines. Germany’s gas transmission businesses submitted a joint plan in July 2024. The plan also considers the feed-in capacity from import terminals and imports of hydrogen derivatives.

Figure 3: Germany’s hydrogen core network (as of July 2024) (Source: Germany’s hydrogen import strategy.

Supportive policy settings

A range of key policies have been introduced to accelerate the build out of this network.

- German law provides for administrative approvals to build, change and operate natural gas pipelines to apply to the transport of hydrogen. However, some administrative decisions must still be applied for e.g. safety and energy law related notifications.

- Planned amendments for the Hydrogen Acceleration Act will include an overriding public interest of hydrogen projects in planning decisions. This will reduce the time needed to seek approval for individual projects that will form Germany’s hydrogen core network.

- The financing model has also been agreed. The network will be financed entirely by the private sector and recovered by grid fees. The initial stages will see grid fees capped to avoid the high grid fees that could be a disincentive as the industry ramps up.

What can Australia learn?

The development of the Australian hydrogen economy is concentrated on a few industry sectors (e.g. ammonia) and creating a local supply solution for the hydrogen demand for that specific business. Germany has a more diverse and chemical and industrial sector and projects high demand for hydrogen to support that sector. A key focus of Germany’s strategy is on building the enabling infrastructure to facilitate a range of local and imported opportunities to meet their hydrogen demands. A future phase of Australia’s hydrogen strategy should consider the benefits of a more interconnected hydrogen play vs local onsite supply and the market this interconnection would create.

[1] https://www.oktoberfesttours.com/oktoberfest/history-of-oktoberfest

[2] The strategy reports between 95 and 130 TWh.

[3] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Hydrogen/Dossiers/national-hydrogen-strategy.html#:~:text=The%20import%20strategy%20complements%20Germany’s,to%20be%20imported%20from%20abroad.

[4] https://hydrogencouncil.com/en/hydrogen-insights-2024/

[5] Low carbon hydrogen is commonly referred to as blue hydrogen and renewable hydrogen is commonly referred to as green hydrogen.

[6] https://www.agora-energiewende.org/news-events/whats-the-timeline-for-germanys-coal-phase-out#:~:text=Germany%20will%20phase%20out%20coal,but%20it%20may%20happen%20sooner.&text=The%20German%20coal%20exit%20plan,by%20the%20government%20in%202018.

[7] https://www.base.bund.de/EN/ns/nuclear-phase-out/nuclear-phase-out_node.html#:~:text=The%20lifetimes%20of%20the%20remaining%20nuclear%20power%20plants&text=The%20Grohnde%2C%20Gundremmingen%20C%20and,2%2C%20Emsland%20and%20Neckarwestheim%202.

[8] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2024/05/20240529-cabinet-clears-path-for-ccs-in-germany.html

[9] Emissions in cement production occurs from the use of coal or gas to provide heat but also from the chemical reaction to produce cement. The reaction emissions represents are an example of an impossible to abate industry.

[10] https://ehb.eu/files/downloads/EHB-2023-20-Nov-FINAL-design.pdf

[11] https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Hydrogen/Downloads/importstrategy-hydrogen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1