Bonn Voyage: are we locked to 3.2°C?

Ministers from around the world and around 25 Heads of State and Government arrived in Bonn yesterday for the high-level segment of the UN climate conference. The United Nations COP23 in Bonn will draw to a close on Friday the 17th of December. Twelve days, 25,000 delegates, mapping out 21 items for resolution, with the Republic of Fiji presiding over the event, held in Germany.

The UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called for more ambition in five specific action areas: Emissions, adaptation to the inevitable impacts of climate change, finance, partnerships and leadership.

Was it a lot of hot air or can tangible measures of success be achieved?

The COP agenda included preparations for the implementation of the Paris Agreement and long term climate finance.

While the Paris Agreement was ratified in 2016, the momentum since has waned, with the United States overtly considering ways to exit. The Paris Agreement stated that countries would reach peak emissions as soon as possible and then make efforts (through Nationally Determined Contributions [NDC] pledges) to reduce emissions to an eventual net zero global carbon emissions in the second half of the century. The intention was to limit global warming to 2°C initially, with a latter, more ambitious target of 1.5°C that would require further emission reductions.

Source: IISD Reporting Services, ENB

The Emissions Gap Report 2017

The UN Environment Emissions Gap Report 2017, released in the weeks leading up to the conference considers the gap between the emission reductions necessary to achieve the agreed targets and the likely emissions from the nationally determined contributions.

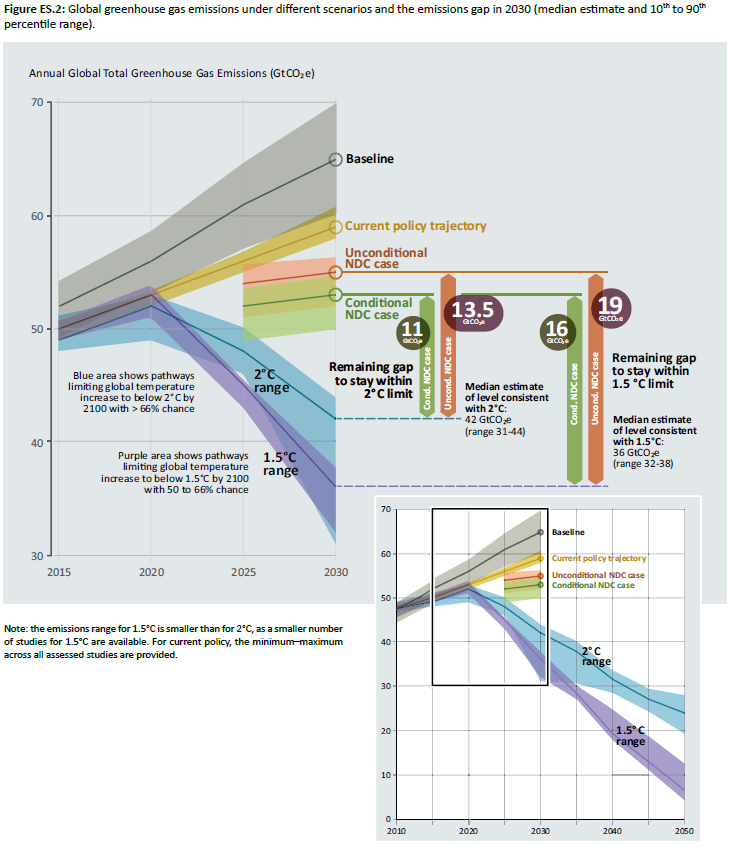

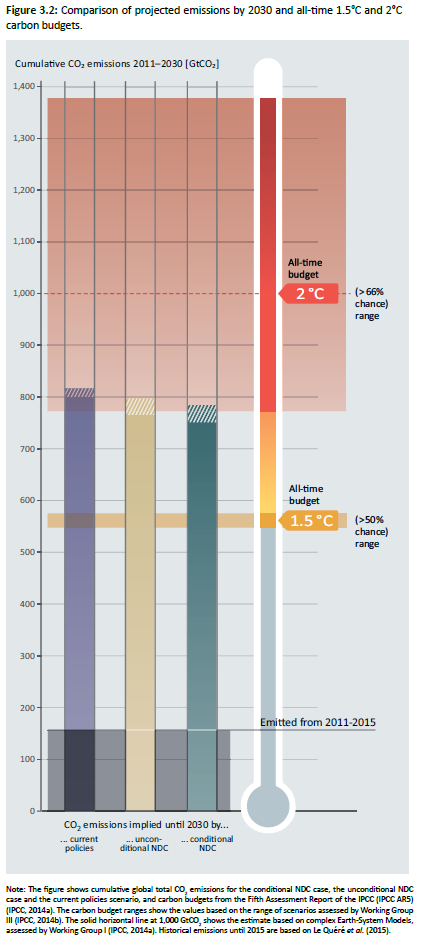

The news is not glowing and the report identifies a lack of action following countries’ reduction pledges. A gap exists between the pledges made in the Paris Agreement and the emission levels required to limit global warming to either 1.5 or 2 degrees by 2100. As it stands, we are on a trajectory for a temperature rise of 3.2°C. Achieving only the existing pledges puts the world temperature well in excess of the 2°C target. Further, the carbon budget required to limit global warming to 1.5°C will be exhausted before 2030 if we proceed along the emissions reduction pathway defined by the pledges.

The chart below illustrates the gap between the NDC and the temperature limits. It is evident that an additional 11 to 13.5 Gt of emission reductions are required to remain on track to limit global warming to 2°C. The chart does not quantify the current shortfall by countries to achieve their NDCs, which is in the order of an additional 6 Gt. It is clear that new policies are needed if we are to reduce emissions by between 17 and 20 Gt CO2 by 2030.

Closing the global emissions gap to be consistent with the 2°C range would require removing all[1] of the emissions from an equivalent of 31 to 36 Australian economies by 2030. Hitting the 1.5°C target would require even more effort.

Source: UNEP, 2017, The Emission Gap Report 2017

The reports demonstrate that the 1.5°C aspiration cannot be achieved if only the NDC are met. Meeting the NDC by 2030 will emit a further 750 Gt of CO2 into the atmosphere and the carbon budget for the 1.5°C target is around 550 GT. Meeting the NDC by 2030 consumes around 80% of the total budget for the 2°C temperature rise making the emission effort beyond 2030 even more challenging.

Source: UNEP 2017

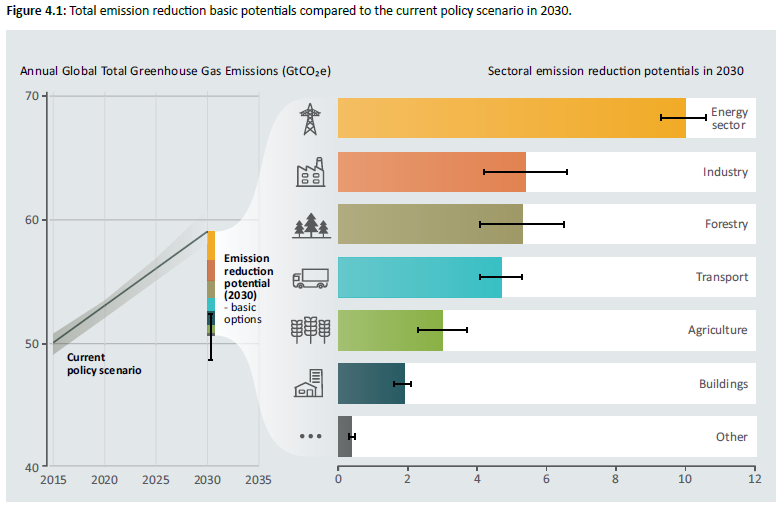

It is clear that the current global NDC are insufficient to meet the global climate objectives of the Paris Agreement.

The UNEP report has identified potential areas where the emission gap to 2030 can be reduced and suggests rolling out proven technologies emission reductions of 33 Gt CO2 by 2030, which is more than enough to bridge the gap to the 1.5°C scenario. These measures are available at a marginal cost of less than USD100/ tonne, the main areas being:

- Solar photovoltaics and wind energy,

- Energy efficient appliances and cars, and

- Stopping deforestation and restoration of degraded forests.

Source UNEP 2017

How is Australia tracking?

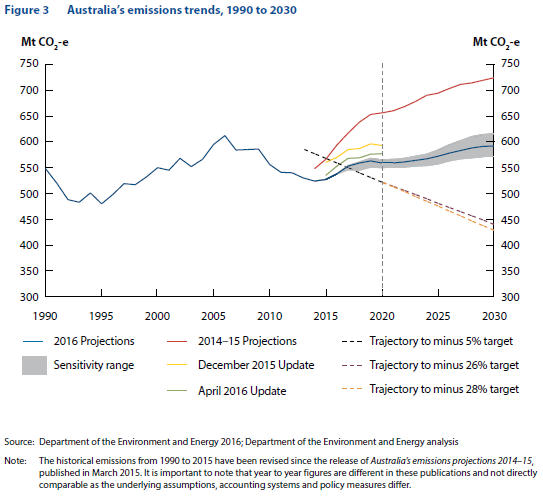

The Australian story is similar to the global one. Our latest emission projections indicate that we aren’t on track to meet the 2030 pledge. Projections suggest that Australia will reach similar levels to those of 2005 as a result of increasing emissions from economic growth. Reaching the 2030 target of 26 to 28% reduction will require additional abatement efforts of approximately 150 Mt CO2 per annum. To put that into context, emissions from electricity generation[2] in Australia were 187 Mt CO2 in 2015.

Source: Department of the Environment and Energy, 2016, Australia’s emissions projections 2016

The Climate Change Authority similarly finds that the 2030 pledge is insufficient to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees. In 2014, they recommended a national target of 40 to 60% by 2030 compared to the Government’s target of 26 to 28%.

Recent focus on emission reductions has been on the electricity sector, particularly schemes such as state based renewable energy targets, a low emission technology target and the National Energy Guarantee. While the majority of these policies focus emissions from the electricity sector, the Emission Reductions Fund primarily achieved cost abatement through the land sector.

While the energy sector[3] contributed 79% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions and the electricity sector contributed 35%, actions to reduce emissions must be adopted across all sectors of the economy, including transport and agriculture. A whole of economy approach is required so that individual sectors are not disproportionately burdened with responsibility for meeting emission reduction targets. However the current political debate, particularly around the National Energy Guarantee tends to focus on a 26 to 28% emission reduction target specifically for the electricity sector rather than the other 65% of national emissions.

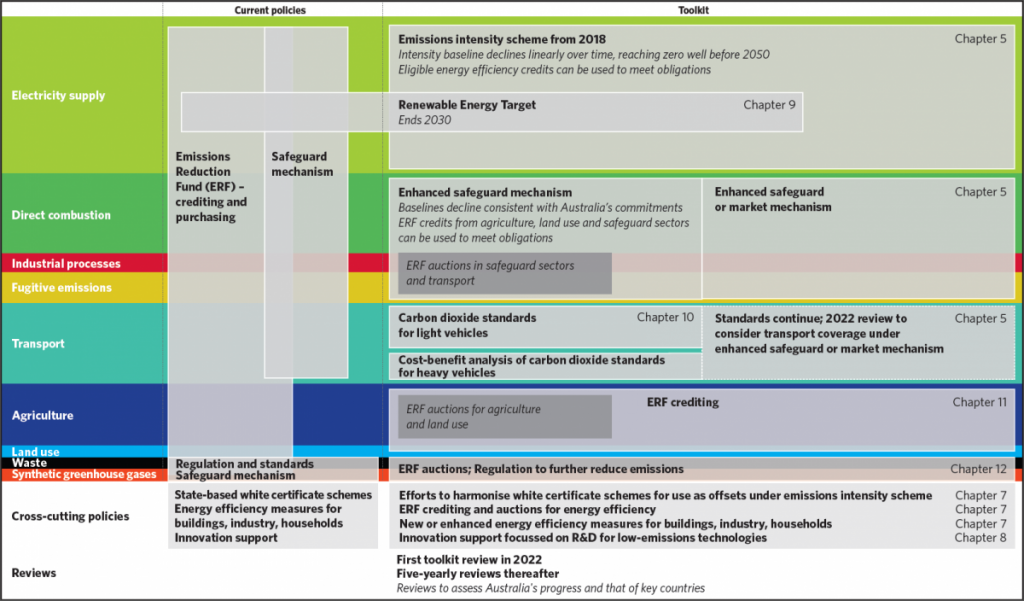

The Climate Change Authority recognised this challenge and prepared a toolkit that was all-inclusive.

Source: Climate Change Authority (2016) – Towards a climate policy toolkit – Figure 1.

Where to now?

Long term observers of international climate negotiations may not be optimistic that COP23s ambition of “further, faster ambition together” is probable in the current environment but it is possible.

The energy sector can play its part to reduce emissions. The Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap and the Gas Vision 2050 represent plausible scenarios for energy networks to enable decarbonisation of the economy whilst ensuring energy security and affordable outcomes for customers.

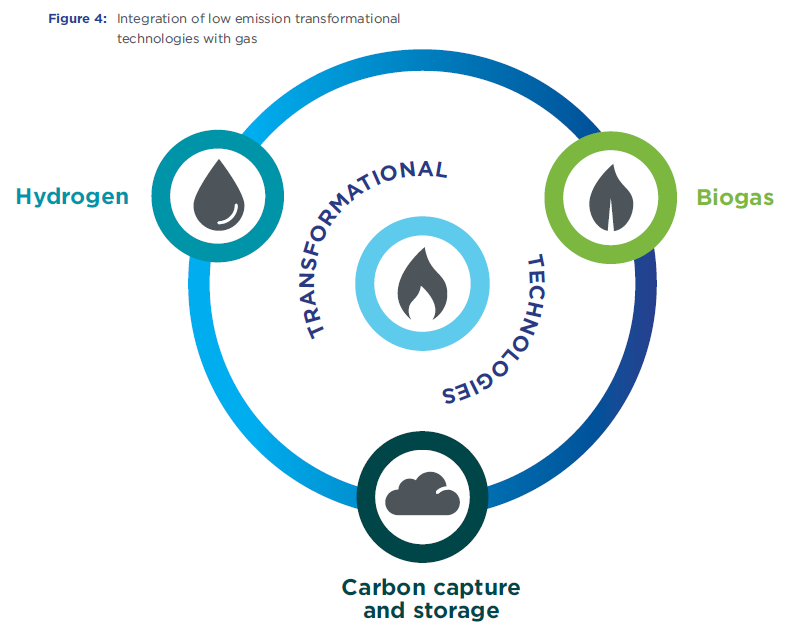

The Gas Vision 2050 focuses on wide deployment of three transformational technologies to decarbonise the domestic use of gas. These technologies are:

- biogas

- hydrogen and

- carbon capture and storage.

Source: Gas Vision 2050 – March 2017

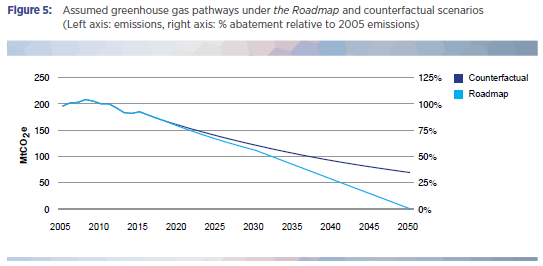

Economic modeling carried out for the Roadmap focused on achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement and indicated that emissions from the sector could be reduced and that the electricity sector could achieve zero net emissions by 2050.

Source: Electricity Network transformation Roadmap: Final Report – April 2017

The gap between actual emissions and those to limit global warming to 2°C (or 1.5°C) is widening and action must be taken to close this gap. The key remains enduring, stable and effective energy and climate policy that ensures energy can be delivered securely, cleanly at the lowest possible cost, with a whole of economy approach.

[1] Australia’s annual emissions are in the order of 550 Mt. A gap of 17,000 Mt CO2 will require 17,000/550 Mt or 31 lots of Australia’s total emissions by 2030. Or slightly more than ALL of the emissions from China and the US combined.

[2] These emissions have decreased in the last two years with decommissioning of coal fired power stations.

[3] Energy sector includes electricity, direct combustion, transport and fugitives.