If we export and import gas, can that benefit customers?

Australia’s LNG industry

About three quarters of the gas produced on Australia’s east coast is exported. Three liquefied natural gas (LNG) liquefaction and purification facilities, known as LNG trains, began operation in Queensland a few years ago and have gradually been increasing their output of LNG for export.

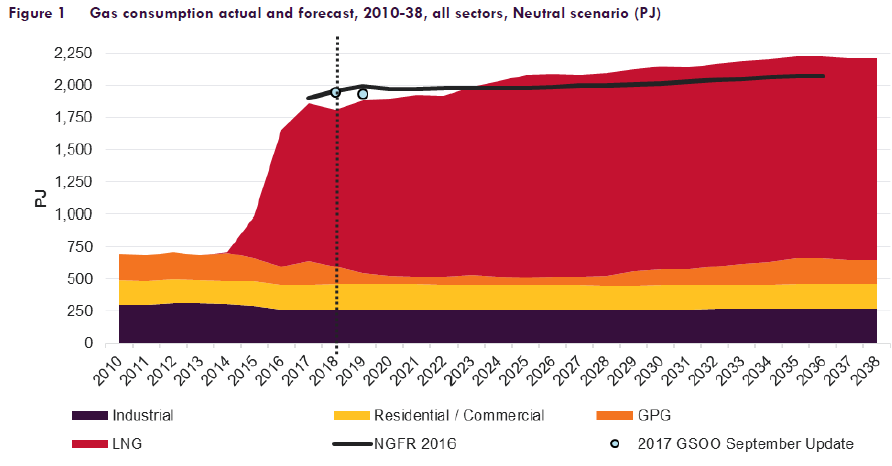

As shown in Figure 1 below, LNG export demand has grown rapidly in the past few years and will continue to grow until the mid-2020s. The variation in domestic demand is mainly a reflection of changes in the use of gas for power generation.

Figure 1: Australia’s east coast gas outlook (Source: AEMO, 2018, Gas Statement of Opportunities).

While east coast production of gas has increased over the same time period, the domestic prices of gas have risen materially following the significant increase in demand.

These rising gas prices are having a major impact on large industrial gas users, particularly those coming off long term contracts, where the gas prices they were paying are much lower than current prices.

The rise in the cost of gas is also affecting residential customers, but to a far lesser extent as falling network charges have resulted in only minor net changes in residential bills.

Many claim that LNG exports have resulted in gas prices being linked to export parity and are solely responsible for gas price increases. While this may have had some impact, there are many other factors at play including:

- The availability of gas

- The cost to produce gas, especially coal seam gas

- Moratoria on onshore gas exploration and production limiting new gas sources being developed to increase supply

- The cost of moving gas via pipeline from where it is produced to the customer.

- Potential government intervention in the gas supply market through the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism (although it is unclear if this has an impact on price).

The Energy Users Association of Australia (EUAA) sees further gas price rises in the next three years, projecting that delivered gas prices could be between $13.50/GJ and $19.00/GJ by 2021[1]. This is higher than the current price range of between $10/GJ and $12/GJ and the EUAA indicates that in the longer term, prices needs to be between $7 and $8/ GJ for large energy users. However, it is unclear whether gas can be produced and delivered at those prices.

Clearly, lower gas prices would be a win for all consumers.

Alternate source of supply

Do projected price rises create commercial opportunities to import gas? Well some businesses think so, and there are five LNG import terminals under consideration in Australia.

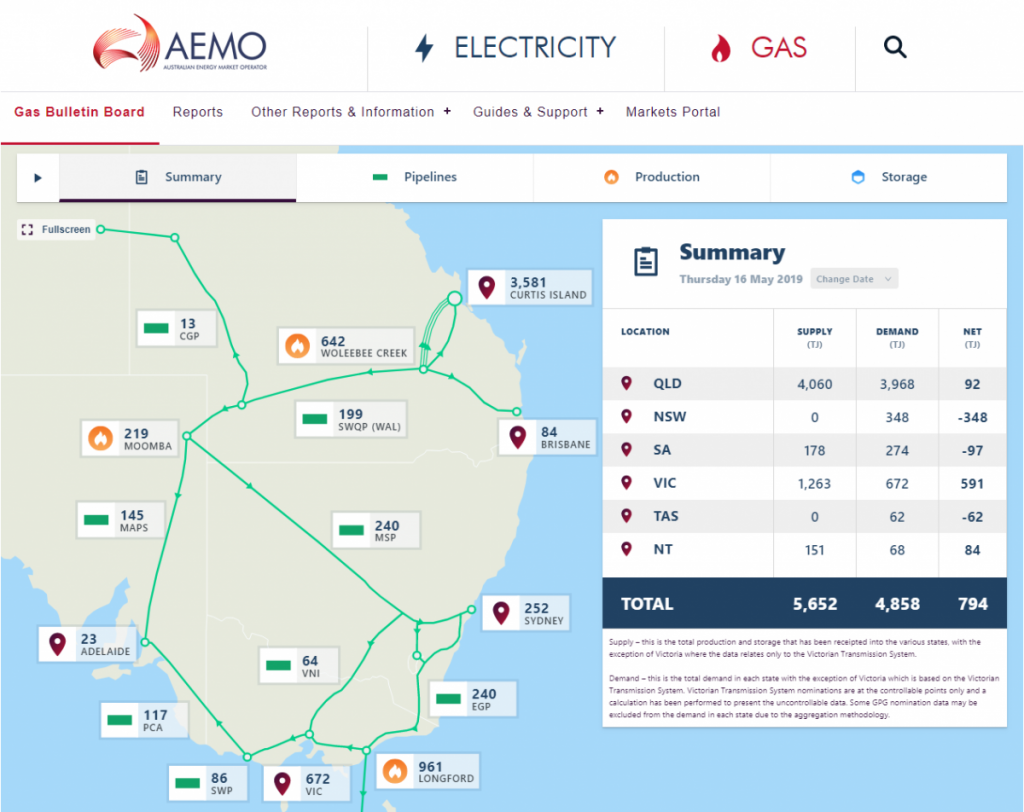

The most advanced import terminal project is the Australian Industrial Energy’s Port Kembla Gas Terminal. The NSW Government awarded development consent on 26 April 2019. NSW has minimal gas production and relies heavily on other states to provide its gas. For example, a recent AEMO Gas Bulletin Board shows that NSW supplied no gas into the system on 16 May 2019 but consumed 348 TJ of gas. This consumption will increase during the colder winter months.

Figure 2: AEMO Gas Bulletin Board (16 May 2019)

Combined, the lack of NSW supply and the potential of decreasing supply means NSW is at higher risk of facing gas shortages compared with its neighbors, who are all significant gas producers. For these reasons, importing gas may make sense.

How does gas import work?

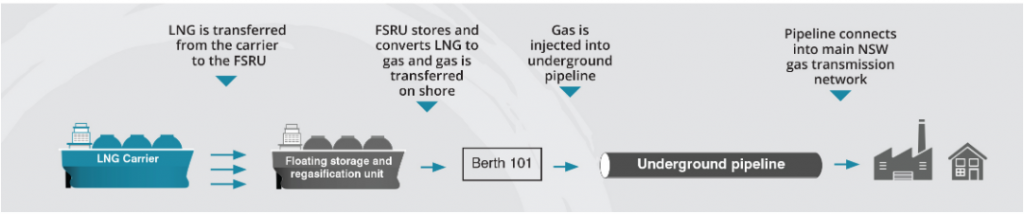

The following image shows how an LNG import terminal project would work. LNG, purchased on international spot markets or via long-term contracts, can be shipped to a port and converted to natural gas via a floating platform (i.e. a second ship) to then be injected into the local gas grid. To make this economically feasible for NSW, the costs of buying the imported LNG and regasification would need to be competitive with the cost of importing gas via pipeline from neighboring states.

Figure 3: Gas imports (source: https://ausindenergy.com/our-project/)

Why import at Port Kembla?

- The planned Port Kembla project will be able to deliver around 100 PJ of gas to NSW per year, or about 70 per cent of the state’s gas consumption

- Having a floating platform and using an existing port facility reduces the amount of new infrastructure required to be built

- Port Kembla is located much closer to the major demand centres in NSW compared with current gas supply, so transport costs would be lower

- First gas can be delivered in 2020.

Importing gas will have flow on effects for existing imports from Victoria and South Australia (note that some gas from Queensland can also be piped to NSW via the Moomba pipeline). Would the additional supply of imported gas into NSW via an LNG import terminal result in gas from Victoria being shipped to Gladstone where it is exported as LNG? Or would it create a surplus in the Australian market that could subsequently lower gas prices? Only time will tell.

In some ways, Australia becoming the largest exporter of LNG and at the same time considering LNG import makes no sense. However, when you consider the geographical size of the Australian market, increasing natural gas production costs and supply constraints, an LNG import terminal could add system flexibility and security.

System flexibility and security helps to ensure businesses can continue to use natural gas and households have a supply of gas to use for heating, hot water and cooking.

Import or export – can everyone win?

The delivered price of gas is a key issue for any project considering importing LNG. Clearly, project proponents of the LNG import terminal at Port Kembla see a business case to compete with the ASX Futures price of delivered gas, especially into NSW. If they are right, hopefully it will keep a lid on rising gas prices – a win for all gas customers.

[1] EUAA National Gas Strategy Options, April 2019, Page 1: “Unfortunately, we see a forward curve for gas at the Wallumbilla Hub (ASX Futures) showing a netback price in 2020 of $10.50GJ rising sharply to $15.00GJ in 2021. With pipeline costs adding between $3.00GJ to $4.00GJ, domestic gas users face a second, potentially more destructive price shock that could represent the “final gas straw”.’