Is Australia ready for the car EVolution?

As the purchase price falls, specifications improve and incentives and infrastructure increase, electric vehicle uptake in Australia will inevitably grow. For a nation of car-lovers, EVs powered by either hydrogen fuel cells or batteries offer a climate-friendly fix for our obsession, with the bonus of decoupling personal transport from punishing petrol prices. The catch is making sure this revolution does not cause a crash for our electricity system and we can all reap the benefits.

The reality is that the huge opportunities from accelerated EV use come with significant challenges. These must be managed to ensure barriers to customer uptake are minimised, cost impacts for electricity customers are managed, the security of the grid is maintained and benefits to the energy market are fully realised.

This issue was a key topic of discussion at Energy Network’s Australia’s Great Expectations: The Interactive Grid seminar yesterday.

KPMG’s paper ‘Electric Vehicles – Is the energy sector ready?’ by Eamonn Corrigan and Sabine Schleicher, explores the challenges, drawing on analysis the firm undertook in 2018 for Infrastructure Victoria on the energy market impacts of 100 per cent EV penetration. Electric vehicles can be either powered by batteries or hydrogen fuel cells.

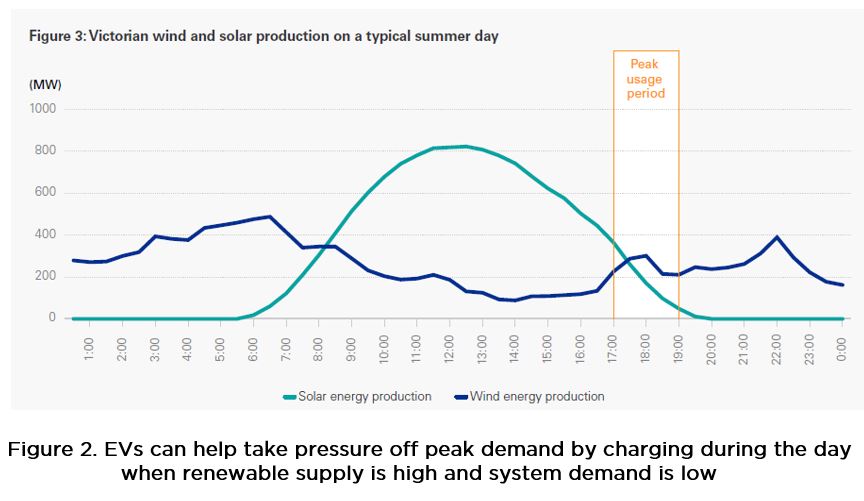

One of the most significant issues for customers and for electricity system security is the impact EV charging will have on the grid if it is not managed or incentivised away from peak demand periods. Peak demand – when customers are consuming the most – tends to occur in the early evening, inconveniently when generation from household solar is not readily available.

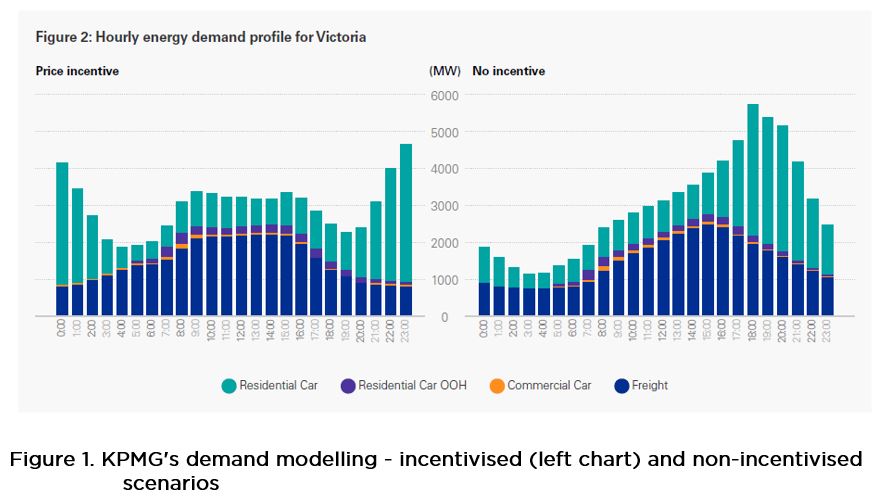

KPMG’s Victorian analysis shows if 100 per cent uptake of battery EVs occurs by 2046, total electricity consumption will increase by about 50 per cent. In a scenario where EV drivers are exposed to price incentives to discourage peak charging, the modelling shows required additional generation capacity of 12,669 MW – 120 per cent of existing installed capacity of the Victorian system. In a non-incentivised scenario, an extra 15,513 MW is needed.

The investment required in generation and network augmentation to deliver this is substantial, but significantly greater in a non-incentivised scenario.

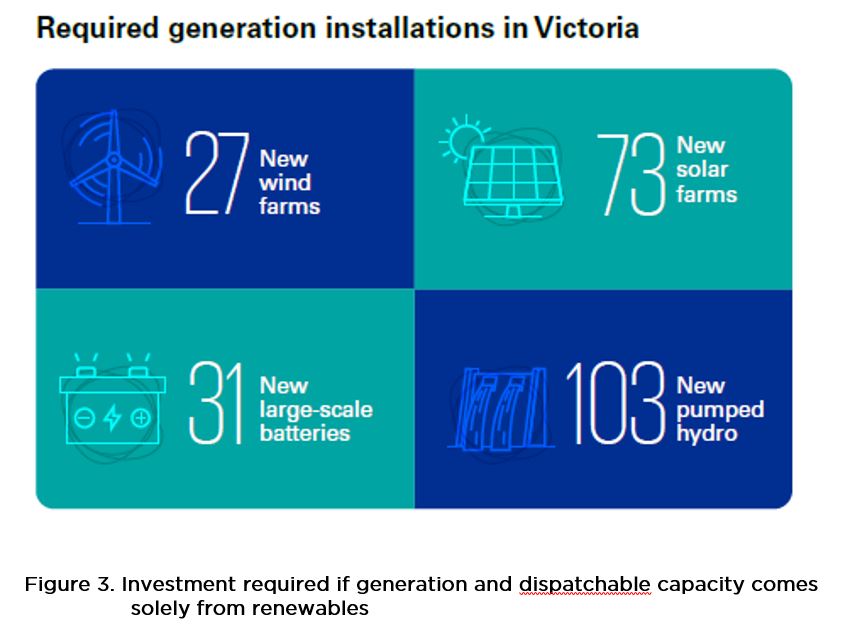

In the report, KPMG points out that if EV uptake is high in the relative near term, before full commercialisation of dispatchable storage like large scale batteries and pumped hydro, there will be great pressure on proven technologies like gas-fired generation to meet peak demand. This reinforces the need for suitable mechanisms to be put in place and for policy certainty to maintain reliability and promote efficient investment.

Cost of EVs to energy markets

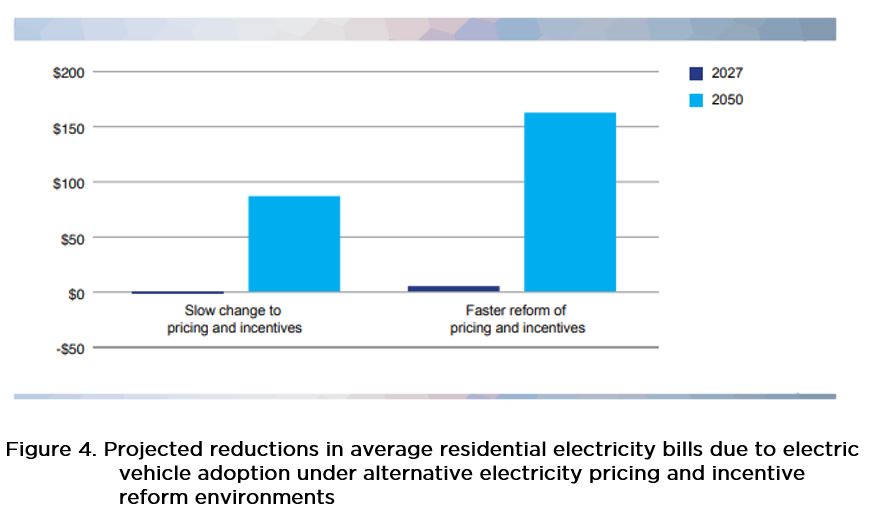

KPMG’s analysis of the cost to the National Electricity Market of a 100 per cent EV uptake is of itself reason enough to make sure we get the integration right. It suggests a NEM-wide impact of up to $22.5 billion. Altering charging behaviour through pricing incentives could deliver a 20 per cent reduction – or $5 billion – in costs.

Without incentivised charging, required generation installations in Victoria alone are significant, however KPMG notes that managing charging into periods when renewable energy is abundant could reduce the required investments.

For electricity networks, the report finds demand from EV charging could lead to a 25 per cent increase in value to account for the required investment, however – the good news – average network prices could fall if charging was incentivised because it would lead to more efficient use of the network. This reflects a conclusion in the 2017 Energy Networks Australia-CSIRO Electricity Network Roadmap Report (ENTR), which found a 40 per cent uptake of EVs by 2050 could see an eight per cent or $162 a year decrease in electricity bills.

The benefits and regulatory challenges of EVs

KPMG’s report highlights the potential of EVs to offset some market costs by either shifting demand or by them serving as a source of power supply and ancillary services (to manage frequency variations) from their batteries. As the ENTR also highlights, uitlising the flexibility of EVs in this way can help avoid network investment and manage the integration of increasing amounts of renewables into the grid.

To maximise these benefits however, reform is needed to the electricity system to ensure Australia’s burgeoning amounts of solar and storage devices can be properly integrated with the grid – which, as our Energy Insider readers will know, is the subject of the Energy Networks Australia and AEMO Open Energy Networks project.

This reform is required so network businesses and the market operator are able to adequately manage supply and demand. A distributed energy world where there is high use of storage devices (which includes EVs), but limited visibility of when batteries are discharging into the grid, is one of unreliable power supply. Multiple batteries discharging into the system at once could cause a local system to trip off because of unmanaged frequency, resulting in localised outages or even potentially compromising whole-of-system security.

Another challenge that KPMG highlights is one almost every key energy stakeholder acknowledges. Tariff reform is essential – in the case of EVs not only to send pricing signals to incentivise behaviour, but in consideration of other issues, like the potential value of bespoke tariffs for EV load.

Another issue of import is transmission capacity. As Energy Networks Australia regularly points out, the logical solution to an increasingly distributed energy environment is greater connectivity. KPMG makes the point that the need for better transmission capacity is especially relevant if there is a significant uptake of EVs powered by renewable energy.

While a 100 per cent uptake scenario by 2046 may seem ambitious, KPMG points out the Clean Energy Council has forecast 95 per cent uptake by 2050 and even the more conservative CSIRO-ENTR estimate is for 40 per cent within 30 years.

Regardless of which forecast proves correct, KPMG points out the uptake is unlikely to be slow and linear. It suggests consumer adoption will follow an ‘S- curve’, where “at some point buying a traditional car no longer makes sense.” It will be at this point, KPMG suggests, that EV adoption will rapidly increase.

Just as Energy Networks Australia advocated in the ENTR, KPMG says government is likely to have a key role in managing market impacts and facilitating the provision of charging infrastructure. Indeed we have already seen Commonwealth and state government funding provided towards fast charging units around Sydney and Melbourne; between Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane and Adelaide and across Western Australia.

Energy Networks Australia also strongly agrees with the report’s conclusion that a clear regulatory and policy framework needs to be in place before EVs take off in popularity to ensure they are able to be ‘efficiently integrated’ into our rapidly evolving energy system and customers are able to reap full benefits.

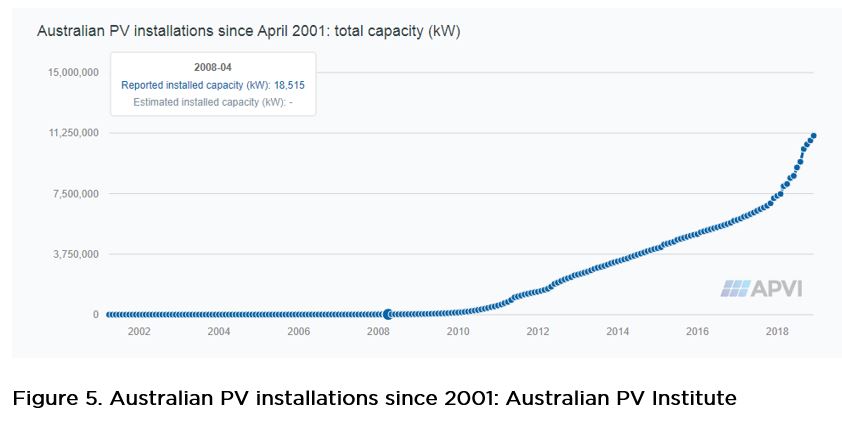

For a hint at what we could be facing, we only need look to the speed and enthusiasm (fueled by subsidies) with which Australia has embraced rooftop solar. In just nine years, Australia’s PV use has exploded from a modest 133,000kw of installed capacity to more than 11 gigawatts (more than two million solar units) by January 2019[1].

If the uptake of EVs is supported by government policy and more incentives and prices for vehicles continue to fall, Australia’s love affair with cars will become far more electric far sooner than we anticipate. We need to be ready for this next revolution.

[1] Australian Photovoltaic Institute Australian PV market since April 2001