Power lines v. Power stations: coming soon to an election near you

In recent weeks there has been cause to speculate what the lasting legacy of the Finkel review might be.

What has emerged is an unusually high profile energy institution- the Energy Security Board – a brainchild of Finkel to implement his blueprint and provide more centralised oversight for energy security and reliability. Agreed to by the COAG Energy Council in July 2017 in the past week the Board has started to interpret its mandate and assert its authority.

The eight-page letter that forms the basis of the Federal Government’s National Energy Guarantee has been heavily scrutinised and details are still emerging. However, this week it was reported that,

…the market operator was investigating the potential for interconnectors as part of a brief from state and federal ministers to improve the security and reliability of the national electricity market..[1]

The ESB report on interconnectors to COAG in December may not just signal a new interconnector for South Australia but also increased capacity between New South Wales and Queensland.

The ESB will also oversee Finkel’s recommendations for greater strategic planning of transmission infrastructure in Australia, including a new planning mechanism – an Integrated Grid Plan (IGP). The plan should “determine the optimal transmission network design to enable the connection of renewable energy resources, including through inter-regional connections.” The first plan is due to be released by the middle of next year. This IGP could subsume AEMO’s annual National Transmission Network Development Plan (normally released every December).

Integrated Grid Plan is the wrong name. One of the criticisms of electricity planning in Australia has been the ability (or lack thereof) of our structures to take a holistic view of developments in generation, network and load in determining the optimal way forward. AEMO’s current process seeks to do exactly that, it should be called an Integrated System Plan as it is about more than just the physical grid.

The Finkel Blueprint anticipates transmission projects will be assessed in accordance with the current Regulated Investment Test – Transmission or RIT-T, recently reviewed by the COAG Energy Council. However, if the RIT-T and market funding sources are not able to deliver beneficial projects required in the Integrated Plan, the Finkel Review proposes Governments should be presented with investment options, to be assessed to be using an economic framework developed by the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC).

This places the need and funding for investment in transmission assets, particularly potential new interconnectors, into the cross hairs of state government plans and election cycles. It may also lead to questioning the efficiency of the RIT-T process.

The heat is on

With five state elections and a federal election likely in the next 18 months the temperature of the energy conversation is unlikely to cool anytime soon. Queensland is the probable first cab off the rank and South Australia’s campaign poll is set for 17 March. Both will have energy policy as a key battlefront.

In South Australia, Labor has a plan, and the Liberals have a solution. The novelty is that technical details that might once have been the realm of engineers and planners are now featuring in key policy documents.

The Weatherill Labor Government’s 2016-17 South Australian Budget committed $500,000 towards a feasibility study to explore options for greater energy interconnection with the eastern states.[2] However the SA Energy Plan released in March this year focused on storage and a new Government-owned gas fired generator.

In contrast, the Liberal opposition has more recently announced a $200 million Interconnection Fund as part of the Liberal Energy Solution. This prioritises an interconnector and the establishment a Renewable Energy Zone between South Australia and New South Wales, as well as proposing to scrap plans to make the government-owned back-up power plant permanent.

The battle lines have been drawn – the SA Government says the national market has failed and is proposing a “go it alone” solution, with the Premier recently saying building a new interconnector was a bad idea.

The Opposition’s policy relies on getting national policy settings right and a more connected future for SA’s power supplies.

The case for a South Australian interconnector?

In November 2016, ElectraNet commenced a RIT-T process to explore the technical and economic feasibility of a new interconnector between South Australia and the Eastern States and alternative non-network options.

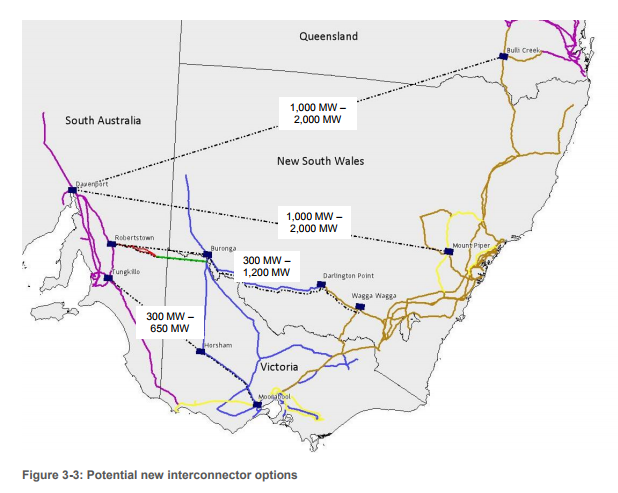

ElectraNet has identified four credible options – links to either Victoria, New South Wales or Queensland which have initial cost estimates of between $500 million to $2.5 billion and “could be operational by 2022, but would only proceed if sufficient benefits to customers can be demonstrated”.

ElectraNet noted at the time that like South Australia countries such as Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom also source a high percentage of their energy needs from renewable generation, but have much stronger interconnection that has enabled its integration. For example Denmark generates more than 40% of its electricity from intermittent (wind) energy but can meet more than 80% of its peak demand via interconnectors with Norway, Sweden and Germany.

AEMO suggests that a South Australian Interconnector would provide significant consumer and market benefits, including:

- net market benefits of $124 to $136 million over the next 20 years;

- greater access to lower cost fuel supplies at times when intermittent generation in the region was low; and

- a reduced likelihood of a widespread blackout in South Australia by mitigating the possibility of ‘separation’ events – where the region is challenged to operate as an island, without relying on synchronous operation with the NEM. AEMO estimated overall net economic benefits of $161 million in resilience benefits in South Australia[3].

AEMO emphasised interconnector investments would be significant and need to be rigorously assessed through the Regulatory Investment Test – Transmission (RIT-T) framework.

However, the market operator also puts these grid investments in perspective – compared to their projected benefits and total system costs, noting that for one particular scenario:

“Total project capital costs are about $1.6 billion in this case, as it includes augmentation of QNI and NSW–VIC as well as the additional South Australia and Bass Strait interconnectors.

This is equivalent to a NPV of $676 million over the next 20 years, when costs are annualised assuming a weighted average cost of capital of 8.76% and a 50 year asset life. For comparison, the NPV of capital expenditure on new generation over the same period is estimated to be $16.4 billion.[4]

Watch this space?

So what does Australia need – more interconnectors or more dispatchable generation? The answer may well be a bit of both and it will certainly vary depending on what’s on the ground already in particular locations. It’s hard to see how a less connected system can reliably deliver the flexible, responsive and low emissions future we need.

While the ESB will continue to progress implementation of 49 of the 50 Finkel recommendations, it may well be the ballot box, not the experts, that determine what comes next for South Australia.

[1] Regulators consider better electricity links, The Australian, 23 October 2017

[2] $500k for energy interconnector study, https://invest.sa.gov.au/news/500k-energy-interconnector-study/#.WfAQeVuCxaQ, June 14 2017.

[3] AEMO, National Transmission Network Development Plan , December 2017, page 30.

[4] AEMO, National Transmission Network Development Plan , December 20167, page 32.