Super sector goes nuclear over energy policy

Industry super funds are calling for investment certainty, long-term supply contracts and an enhanced market operator in a recent report critical of Australia’s energy policy – or lack of it. Modernising Electricity Sectors is a critique of the energy policy framework which explains that the current state of minimal direction from policy makers can mean even long horizon investors are struggling to invest in the system.

As holders of $3 trillion worth of Australians’ retirement savings and with a duty of responsibility to their members, super funds have a strong interest in guiding policy towards successful long-term outcomes. They are ready and waiting to pump capital into the electricity sector.

But, there is a problem

The long-term, technology neutral energy policy which deals with reliability, competitiveness and emissions has not been forthcoming. Without it, investors don’t have enough certainty to confidently invest.

Large-scale changes will be necessary if the energy system is to adapt to a lower emissions future. Even without emissions reduction, Australia’s aging coal-fired fleet will need to be retired. Super funds posit that continuing down the business-as-usual path on which Australia has been heading for some time, would lead to short-term investments taking advantage of capacity gaps, an economy plagued by stagnation and ‘severe to extreme’ reductions in productive capacity.

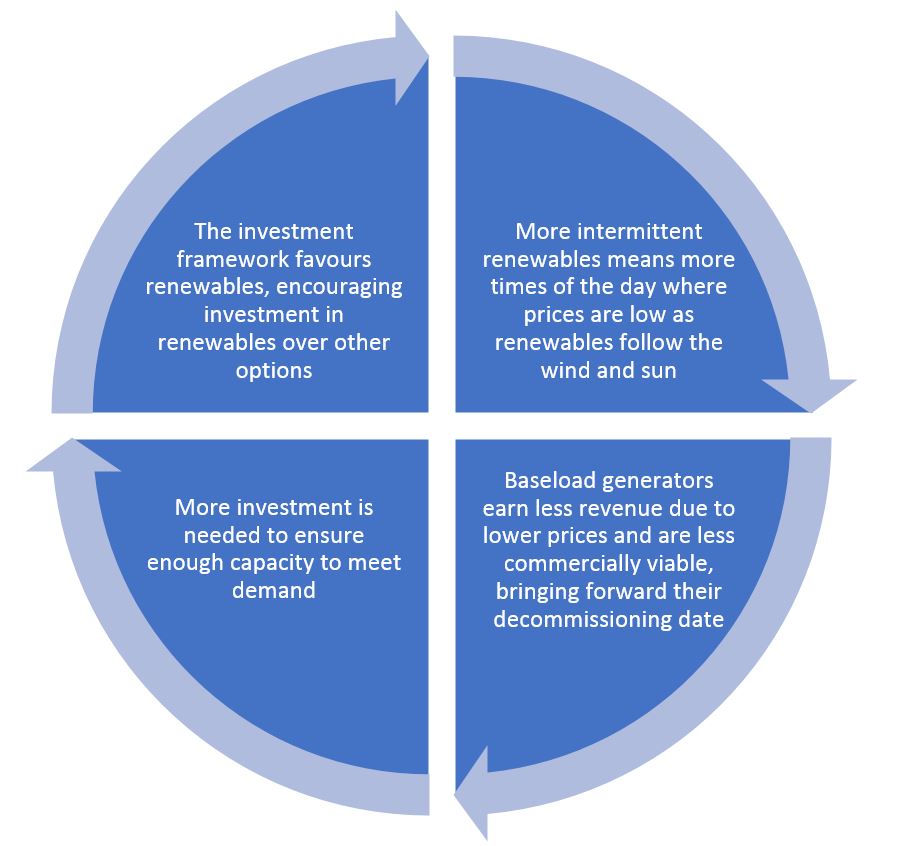

The report claims that ill-fitting policies steer investment towards long-term infrastructure that are only viable due to subsidies, with the negative cycle reinforcing itself over time:

Super funds argue that the stark reality of this cycle is that in the absence of policy changes, it may continue for decades, raising prices and increasing the prevalence of blackouts.

But there is a solution

In a challenge to the current energy sector state, super funds are pushing policymakers towards a path which would see Australia establishing a long-term technology neutral investable framework while reducing emissions levels.

They say policies should be steered towards meeting objectives which must be met in order to reach a stable economic state, or in other words, an economic state which reinforces a positive cycle of investment, instead of the negative cycle outlined above.

A technology neutral policy would allow energy technologies to be chosen on merit, rather than the strength of competing subsidies and would allow other undeveloped technologies the same opportunity to be established.

With a focus on the long-term, one suggestion made is that rather than focusing on the spot market for energy pricing, the National Electricity Market should be focused on creating competition for the long-term supply of capacity and energy at given emissions targets. Under this model, contracts of 20 years or longer could be sold through auctions to provide certainty to long-term asset equity owners which would encourage investment in energy capacity based on merit.

In tandem with some form of proposed carbon pricing, Industry Super argues this would provide an investment framework with certainty, technological neutrality and incentives for decarbonisation. Long-term supply contracts are also proposed to be formerly underwritten by Government on the basis that if emissions are higher than acceptable, Government could then – it is argued – step in with policies which encourage low-emissions generation.

Enhanced market operator?

There is a trade-off between investing in network infrastructure and investing in generation assets. Investing in network infrastructure facilitates better transportation of electricity between markets, whether it’s Victorian generation powering Queensland or local customers trading their solar. This improved interconnection leads to a more competitive wholesale market.

Industry Super points out investment in generation infrastructure also increases competition in the wholesale market and leads to lower prices through competition. However, the Australian Energy Market Operator’s 2018 Integrated System Plan (ISP) points out that additional transmission investment (rather than replacing retiring coal-fired generation with new generation and not building new transmission to increase network capabilities), could conservatively deliver about $1.2 billion in net present value.

The super funds argue that major reform is required and that such decision making should be empowered to a public body charged with making decisions in the national interest. This view goes hand-in-hand with suggestions that 20-year contracts should be underwritten by government. Decisions on investment in network maintenance and expansion would fall upon this entity.

In a narrow sense, this isn’t a radical suggestion given networks carry out planning already to operate the grid efficiently. Each network’s revenue determination, including detailed capital and maintenance plans, requires approval by public regulators. The report fails to reflect this key component of the existing framework.

Transmission networks also input to broader joint planning frameworks – like the ISP – which attempt to coordinate investment in networks and generators. What the super funds are proposing is a significant step further and could be interpreted as asserting a case for ‘public ownership’ of a vertically-integrated generation and network sector, at least in a decision-making sense.

A central planner could potentially result in generation assets and network infrastructure being closer aligned than they are today, but it might not add that much value in practice. Indeed, many elements of today’s grid are a legacy of such central planning style models having been implemented in the past. Network businesses are subject to independent regulatory determinations which already ensure efficient investment decisions are made in the public interest.

Development of the NEM comprised moving decisions outside of the closed corridors of single central bodies into a more contested, transparent process. The rules which govern networks and generation are evolving to maintain currency as time moves on. Centralising these decisions under the report’s proposed framework may result in similar decisions being made, but without the visibility and stakeholder engagement required under the current framework. Not to mention the large and burdensome transition costs.

The UK’s OFGEM has previously considered an independent transmission system operator under its Integration Transmission Planning and Regulation project but decided against giving the body power to make investment decisions. If a stand-alone independent planner isn’t yet assessed as feasible in the UK, which has a richer, more interconnected and denser market to support the cost base, then there are at least questions about its feasibility in Australia.

Take-aways

It’s clear that super funds seek market reform to provide better certainty to investors. After all, they aren’t the first party to suggest that more long-term certainty is needed and in the current policy context they won’t be the last. It’s not surprising it was the decision to leave nuclear on the table that got much of the media attention – “investors want more certainty” is not front-page news.

Even in the absence of long-term policy there is still a role for super funds to finance development of new technologies in pursuit of long-term cost reduction, capacity provision, reliability and emissions reduction.

The industry is in a politically-contested policy vacuum and the report’s existence alone speaks to the point that momentum for change is growing. Super funds are lining up capital in preparation for when a suitable investment opportunities emerge.